The Visual Culture of Privacy

I think we can all agree on one fact, that the average contemporary individual – and I would definitely include myself here – has almost no idea about anything. Today everybody seems to be accustomed to a certain lack of understanding, especially in the realms of natural sciences, medicine, or economics, but also when questions are raised about history, culture, or politics. Utter cluelessness in the face of things and circumstances has developed into a state of being. Yet, however unsettling this human condition may be, it does not pose a serious problem in our private lives, quite the opposite. What is not understood when looking at the big picture can be substituted by generating sense out of small things and images. Cluelessness offers the benefit of reducing complexity and of lowering the degree of expenditure and accountability. The awareness of one’s own limitations is rarely seen as a loss, but rather considered as a chance to liberate oneself from the many alarming news and to refrain from a tiresome engagement in the incidents of an outside world. This segregation opens passageways to envisage and acquire an alternative history that feels grand in its constriction and even heroic in its stubborn avoidance[1] – the individual archive.

Little Red Riding Hood, around 1960

Personal images and small objects are collected to allow for different simple and pleasant narratives that can banish feared alienation by creating notions of “home”. These cosy retreats are predominantly governed by a visual culture of self-assurance that displays the claim, or even better, the right to a life and afterlife in all kinds of knick-knacks and photographic images. This proliferation of self-empowerment and self-documentation and its promise to shape and sell individual histories as something universal is dialectically opposed to the role of a collective cultural history that is in turn diminished.

Cheap cameras, like those produced by the Eastman Kodak Company for example, became a widespread commodity because it made the recording of personal moments an easy task, and because every picture consolidated one’s own wish for lasting memories.[2] The crisis of a ‘general history’ can be seen as a result of the proliferation of individual histories. Acquiring one’s own picture can be understood as a hegemonic gesture, an implementation of a visual regime that serves to bring the private sphere into a picturesque order and to arrange the small world as a defensive place to unfold one’s own individual historicity. In this respect, the stereotypical images of happy families in tidy homes carry a political agenda; they do not reproduce the reality, they instead recycle clichés. The economic potential of amateur photography stems from the promise to display and represent a pacified domestic “heterotopia” that is filled with narratives of beauty, pleasure, and innocence.[3] In the ideological centre of this visual culture of small objects, cute things, and sentimental images lingers the wish to avoid any uncertainty and to escape from the presumed dangers of the outside world.

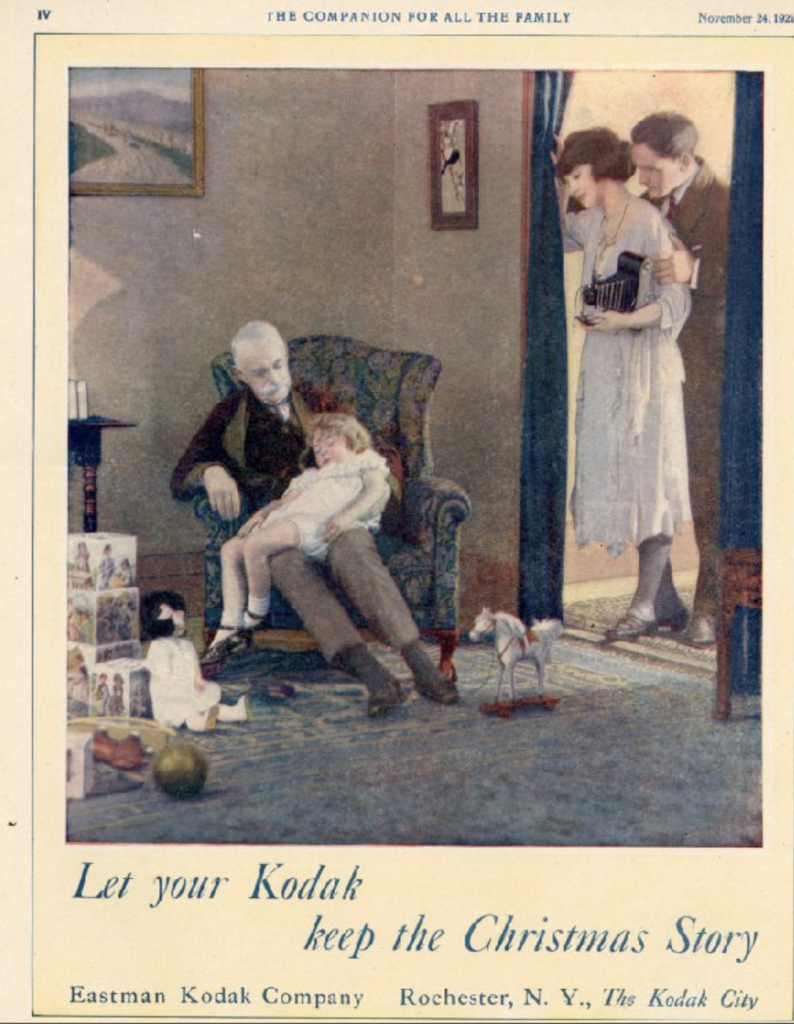

Kodak Advertisement, 1921.

Nancy West has shown that the Eastman Kodak Company was one of the first firms that promoted what she calls “photography as privatized memory”.[4] She writes that “From the beginning, snapshots were intended to record events worth remembering mainly for the fondness of their happy emotional messages.”[5] Sadness, disruption, or personal disaster had no place in the snapshot craze and the many emerging picture archives. To a large extent, what she calls “the snapshot aesthetic” of the early twentieth century was soaked in “bright sentiment”.[6] The present was kept in carefully staged images that were purposefully taken to enable future narratives of a better past. Like keepsakes, snapshots offered and still offer “consumers the means to ‘preserve’ their memories”[7] and unlike other commodities such as newspapers, magazines, or fashion items, photographs capture a transitory moment in time to create “a lasting product whose value continues to grow over time as it becomes imbued with nostalgia when viewers long for the ‘happier, simpler times’ depicted in their snapshots”[8] of people, places, and events.

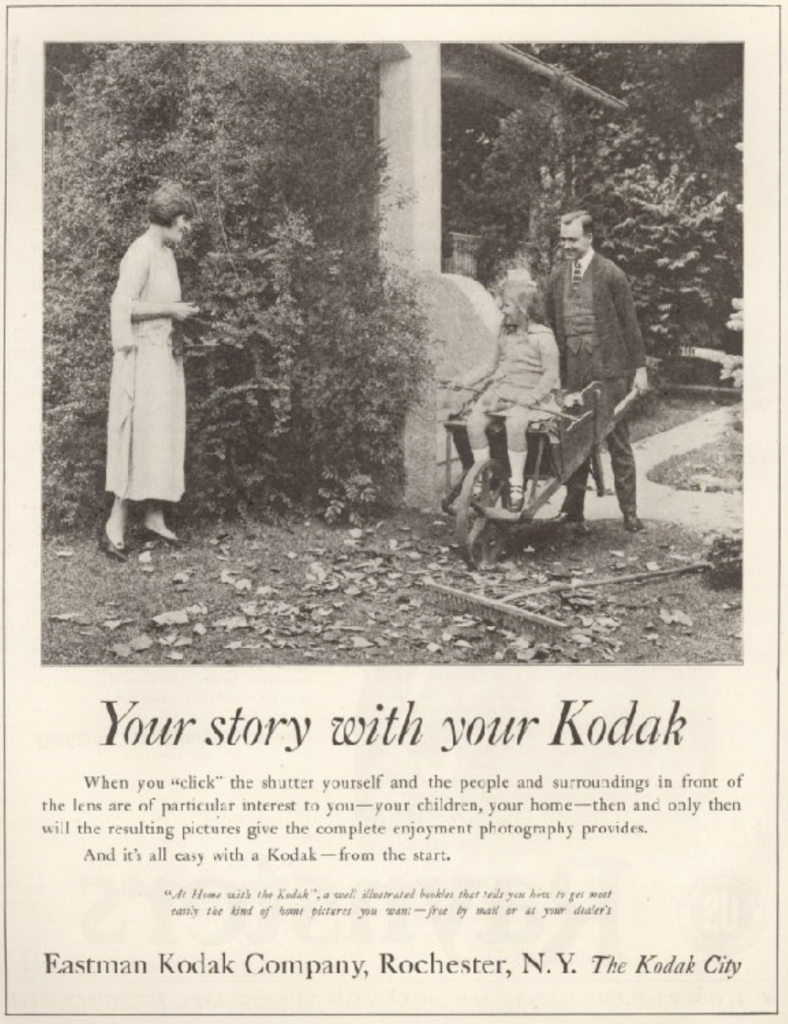

Kodak Advertisement, 1922.

What is documented in these pictures are the supposedly great moments of a private life, assembled to hold the once invested emotions in stock for later refreshment. It is the recollection of the picturesque past that plays a major role in constituting the private sphere called “home”. To gaze at the images on the credenza or to leaf through the notorious albums of photographs can open doors to an enjoyable regression and may also generate a form of self-confidence that is detached from and therefore immunized against external threats.

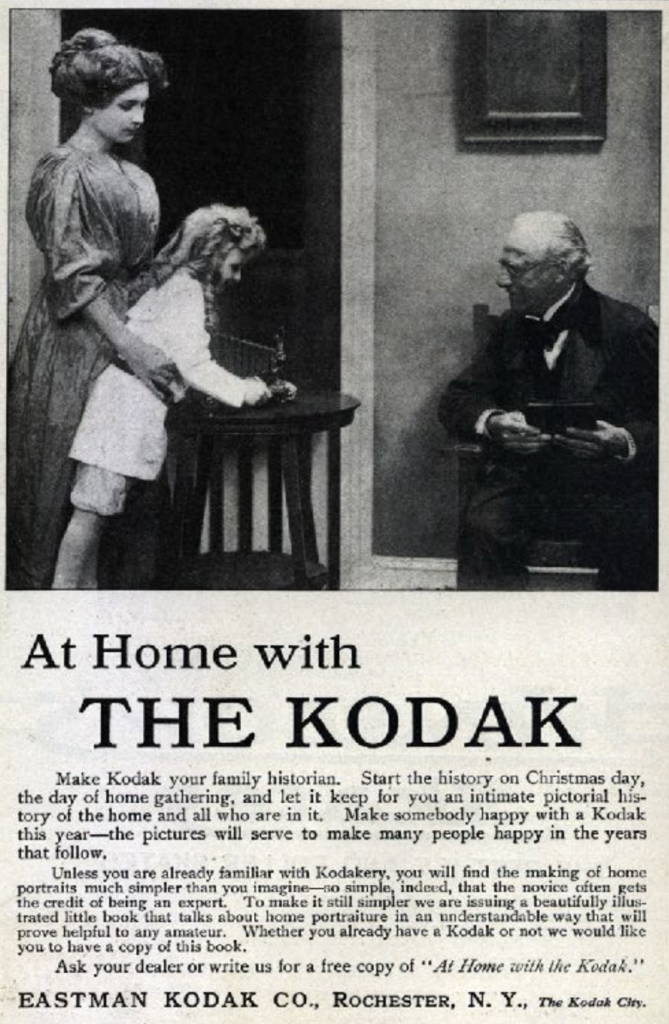

Kodak Advertisement, 1910.

At home, historical stereotypes and anthropological constants blur together. The wish to escape into a better world stands behind the labour invested in the private archive. Everyday experiences are eternalized in photographic documents that pretend to exhibit singularity and individualism, but show only the recycling of poses broadcasted in advertisements and commercials. The amateur archivist pours common sentiments into images of idiosyncratic importance, driven by the urge to shape the family’s micro-history and to present it to others as unique and immaculate. In the advertising series called “At Home with Kodak” from 1910, the mother is assigned a new role, to be the family photographer and also the creator and keeper of the family album. The slogan of the advertisement proclaims the importance and potential of the photographic moment: “Make Kodak your family historian. Start the history on Christmas day, the day of home gathering, and let it keep for you an intimate pictorial history of the home and all who are in it.”[9] Just by pressing the button the snapshot becomes „family history“[10]

The downside of such a commercialized mnemonic enthusiasm can be found in the fact that, most of the time, family pictures are – as we all know – dull objects when it comes to questions of taste and composition. They are mostly characterized by a lack of formal appeal and aesthetic value. The reason for this seems to be that these pictures are first and foremost taken to shape and deliver a cliché of domestic bliss and are framed and assembled to establish a space for private narration. Such artefacts display a specific content whose function is to allow for nostalgic recollections of a past that was intentionally cleansed from all dirty spots. The whitewashed family record follows normative expectations of what a household should look like and what it should represent and stand for. Such images contain and transfer poses of what the philosopher Hans Blumenberg would have called “fortune-assurance”. They reveal the will to document and store customized visions of brighter aspects of private life to be recalled later. Out of accumulations of kitschy objects, sentimental keepsakes, and family snapshots emerges the sweetness of what is called the “sweet” bourgeois home. From the collection of supposedly authentic memories emanates the protective certitude of owner- and authorship that transforms the home into the proverbial castle – an escapist refuge stuffed with objectified occasions for self-narration.

The reification of emotions and memories can be described as an anthropological constant and a cultural technique uncoupled from the privileges of birth or the prerogatives of class. The appreciation for small things that were once charged with sentiments is found across all times and in all societies – the curl of the loved-one in the locket, the photographs of the children in the wallet, and on every sideboard and shelf all kinds of souvenirs,[11] for example cute objects that venerate the loved grandmother. The embellishment of one’s own history leads to the construction of emotional frameworks, which provide dubious stability and precarious permanence. Surrounded by images and objects that were formerly charged with sentiments and narratives, people tend to lose sight of their own deficiencies. In such cocoons of materialized traces of manufactured emotions, the feeling of general cluelessness fades, and understanding for the other or the world is substituted by a personalized and unique knowledge about the origin of the things that constitute personal history. Here one feels at home, here everything is familiar, here are stories to be told. In such a private sphere reigns an autonomous and subversive taste, an attitude to beauty that self-confidently undermines any aesthetic norm or modish regime. In such places some kind of decorative autarchy jointly rules with a form of sentimental autism to foster a benevolent inclination for kitsch and knick- knacks that defies all rational approaches and mocks the complaints of critical theory. Family pictures and kitschy paraphernalia can be historically understood as an ongoing resistance to the requirements of a modern society. The images and objects stand for a comforting regression in the face of forced surges of innovation, and point to the conservative renitency of the average picture archivist. To wrap it up in a sentence of the German philosopher Hermann Lübbe: “The more thoroughly a technological and scientific civilisation establishes its own legitimacy, the stronger the reactive wish becomes to escape its immanence through the self-commitment to ideals that transcend this legitimacy.”[12]

In contrast to the efforts of an artistic avant-garde that champions progress and innovation, the visual culture of private spheres constitutes itself mainly through the longing for tradition and conservatism. To dwell in an accumulation of – what I would like to call – re-collectables entails the negation of the attempt to understand and qualify a changing world “out there”. At home one prefers to delve unconsciously into the comfort of intimate objects and pictures that display possible narratives of a former emotional and mnemonic investment. “The souvenir involves the displacement of attention into the past,”[13] writes Susan Stewart. This joyful regression has the appearance of autogenic training and is close to what Theodor Lipps once coined “objectified self-enjoyment”.[14] Such a practice has to be sectarian in nature and is characterized by the inclination to retire from public life into a realm of authenticated images that radiate the aura of personal truisms. To quote Vilém Flusser from his book Towards a Philosophy of Photography:

„Images are mediations between the world and human beings. Human beings ‘ex-ist’, i.e. the world is not immediately accessible to them and therefore images are needed to make it comprehensible. However, as soon as this happens, images come between the world and human beings. They are supposed to be maps but they turn into screens: Instead of representing the world, they obscure it until human beings’ lives finally become a function of the images they create. Human beings cease to decode the images and instead project them, still encoded, into the world ‘out there’, which meanwhile itself becomes like an image – a context of scenes, of states of things. […] Imagination has turned into hallucination.“[15]

In this sense, friends of kitsch, knick-knacks, and sentimental self-documentation in photographic images abide in the seclusion of their domestic ambiance and develop an autonomous taste that is often generalized and then projected outwards as an aesthetic assertion. This literally home-made visual culture of intimacy tries to colonize the outside world with an idiosyncratic aestheticism. As already mentioned above, sentimental re- collectables are often assembled in museum-like arrangements, to display and account for the emotional history of a person or a family. As an example I would like to show you a Canadian household in which I had the privilege to be a guest on several occasions. This home was cramped with small and often vintage objects, things of a long gone popular culture, like figurines from the 1950s and 60s.

Mr. Salt and Mr. Pepper, circa 1960.

Especially the kitchen was decorated with plenty of non-functional stuff. As just one remarkable example, consider Mr. Salt and Mr. Pepper, two eggs dressed up in formal attire whose appearance, facial expression, and posture can probably only be described as outlandish or weird – they definitely must remain a riddle for trained art historians. What is visible at first glance is the neglect of the figurines. Judging by the layer of dust on their bald eggheads, it is obvious that these fellows have been off duty for the longest time. Without their accustomed roles, Mr. Salt and Mr. Pepper are degraded to live out their lives as cute ornaments. The one and only function they still have is to attest to a long vanished household reality and to provide an interesting face and narrative to a specific period in time. What could be told here, however, has nothing to do with the objects themselves, nor with the aesthetic value of the figurines. The quality of these salt and pepper shakers lies in their potential to trigger the recollection of a cute and – back then – supposedly funny gesture, a little story that, with a gentle push, can be unfolded into an all-embracing tableaux of family history.

One of the astonishing features of the visual culture found in kitschy things and cheesy pictures can be seen in the fact that they tend to fall into invisibility. One does not pay attention to these materialized testimonies of happier moments any more, and they are absorbed into a visual sedimentation that creates a kind of wallpaper of memories. These re-collectables are stored for occasions of self-assurance and can be activated when something has to be shown or told again. This is also a very practical process, because the accumulation of kitsch establishes spheres of deliberate relaxation and inattentiveness, spheres that are extensions of the self and therefore stuffed with objectified incentives for tales, legends, or anecdotes, spheres where one does not have to think, but can remember something if necessary. Purposefully overlooked, these visual stimuli display and attest to family history without the need to continuously narrate it anew. The unfolding of the potential narratives does, however, require people to lend their affection to the exhibition of objects and pictures.

While some of the re-collectables in our Canadian household show remnants of political convictions and religious beliefs, or appear to have been presents, some other’s function seems only to point towards a domestic commemorative culture – with strange ensembles that come as pure decoration, for example the abundance and welfare suggested by a bunch of plastic grapes, or the plate of synthetic vegetables indicating healthy nutrition or vegetarianism.

Allegory of Healthy Food, around 1995.

The materialized attempts of fortune-assurance visible in such objects can also reveal tragic aspects when the potentiality of the narratives falls into oblivion or no one is left at home to activate them. The status of kitsch and photographic images becomes precarious where the archivist of a collected family history vanishes and what was once used as an emotional retreat becomes a repository of objects that are somehow hollowed-out.[16] Nancy Martha West concludes that, without an accompanying story, “photographs can denote historical bankruptcy, their silence, fragility, and sheer profusion stubbornly resisting any attempt to assign them an intimate meaning.”[17] But once freed from the function to account for a former emotional state or a happy memory, these things begin to speak about their own material qualities. The detachment from a specific historicity brings the object-hood of kitsch or photographic images to the foreground. When the value of personal meaningfulness is gone and the emotions and memories have no addressee anymore, the paraphernalia begin to qualify as cheap and gaudy, as sweet and sentimental. They change their character from self-defining souvenirs to a pile of waste. Cheap photo albums in flee-markets attest to this point. Marina Benjamin notes that, after all, „one family album looks much like another, bound within the codes of commemorative convention. Rainy days, tearful arguments and black sheep are omitted. Only smiling faces and sunshine are double-glazed in octavo, reproducing for private consumption the public faces that the family presents to the world.“[18]

Richard Billingham, “Ray’s a Laugh”, 1996.

It is exactly the opposite approach that lends the family photographs of the young British artist Richard Billingham their shocking attractiveness. The series “Ray Is a Laugh” plays with the expectations that the trained amateur archivist brings to images of families’ self-documentation. They purposefully contradict the requirements of a commercialized photography that pretends to be a commodity, but is instead just another tool to imprint an average household with political ideas of how to administer the stereotype of a supposedly good life. Everything seems to be in the right place: the figurines in the cupboard, the framed portrait on the shelf, the pictures on the wall, all the markers of the sedimentation of an emotional history. But what remains absent is the urge to hide the ugly sides of family realness behind the screens of the staged simulacra of a reality that is recycled from a public domain. Billingham’s intimate pictures nonetheless attest to the assumption that small keepsakes and photographic souvenirs are accumulated to construct private spheres of security and knowledge in a world that leaves us puzzled and clueless. Private archives are assembled to lower the level of complexity we have to deal with and therefore the visual culture of “home” tends to cultivate an alternative historicity, a historicity that feels grand in its constriction and even heroic in its autonomous taste.

Remarks

[1]Stefan Germer, “Mit den Augen des Kartographen – Navigationshilfen im Posthistoire”, in: Kunst ohne Geschichte? Ansichten zu Kunst und Kunstgeschichte heute. Edited by Anne- Marie Bonnet and Gabriele Kopp-Schmidt. Munich: C. H. Beck 1995, 140–151, esp. 148.

[2] See Richard Terdiman, Present Past. Modernity and the Memory Crisis. Ithaca, N. Y.: Cornell University Press 1993, 13.

[3] Nancy Martha West, Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia. Charlottesville and London: The University Press of Virginia 2000, 10.

[4] West 2000, 13.

[5] Douglas Collins, The Story of Kodak. New York: Harry N. Abrams 1990, 121.

[6] Collins 1990, 121.

[7] West 2000, 9.

[8] Nicola Goc, “Snapshot Photography, Women’s Domestic Work, and the ‘Kodak Moment,’ 1910s–1960s”, in: Home Sweat Home. Perspectives on Housework & modern Relationships. Edited by Elizabeth Patton and Mimi Choi. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield 2014, 27–47, esp. 33.

[9] Cited after Goc 2014, 41.

[10] Kodak ad in Life Magazine.

[11] Susan Stewart, On Longing. Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press 1984, 151: “The souvenir is not simply an object appearing out of context, an object from the past incongruously surviving in the present; rather, its function is to envelop the present within the past.“

[12] Hermann Lübbe, “Der verkürzte Aufenthalt in der Gegenwart. Wandlungen des Geschichtsverständnisses”, in: ‘Postmoderne’ oder der Kampf um die Zukunft. Die Kontroverse in Wissenschaft, Kunst und Gesellschaft. Edited by Peter Kemper. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag 1988, 145–164, esp. 156: “Je reiner sich die technisch- wissenschaftliche Zivilisation in ihrer Eigengesetzlichkeit durchsetzt, desto stärker wird der reaktive Wunsch, ihrer Immanenz durch Selbstverpflichtung auf Ziele zu entkommen, die ihr transzendent sind.”

[13] Stewart, 151.

[14] Lipps Theodor, “Einfühlung und ästhetischer Genuß”, in: Emil Utitz, Ästhetik. 2. Auflage, (= Quellenhandbücher der Philosophie) Berlin: Pan-Verlag, 1924, 152–167, esp. S. 152: “Es gibt drei Arten, genauer gesagt, drei Richtungen des Genusses. Ich genieße das eine Mal einen von mir unterschiedenen dinglichen oder sinnlichen Gegenstand, zum Beispiel: den Geschmack einer Frucht. Die zweite Möglichkeit ist die: Ich genieße mich selbst, zum Beispiel: meine Kraft oder meine Geschicklichkeit. Ich fühle mich etwa stolz in Hinblick auf eine That, in der ich solche Kraft oder Geschicklichkeit an den Tag gelegt habe. Zwischen diesen beiden Möglichkeiten aber steht, beide in eigenartiger Weise verbindend, die dritte: Ich genieße mich selbst in einem von mir unterschiedenen sinnlichen Gegenstand. Dieser Art ist der ästhetische Genuß. Er ist objektivierter Selbstgenuß.”

[15] Vilém Flusser; Towards a Philosophy of Photography. London: Reaction Books 2000, 9– 10. See Jacques Lacan, Die vier Grundbegriffe der Psychoanalyse. Das Seminar von Jacques Lacan, Band XI (1964). Olten und Freiburg im Breisgau: Walter 1978, 81.

[16] West 2000, 8.

[17] West 2000, 175.

[18] Marina Benjamin, “Picturing the Silence”, in: New Statesman & Society 25.06.1993, 32– 33. Cited after Stephanie Nickel, Betrachten, Bewahren und Beweisen: Familienfotografie als Lebensspeicher. Berlin: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin 2014, 96.