Perfume as Olfactory Supplement in Pop Music

[aus: »Pop. Kultur und Kritik«, Heft 15, Herbst 2019, S. 161-176]

Perfume is pervasive. And so is pop culture. However, perfume in particular and scent or odor in general still lead a miserable existence in pop theory and pop discourse. The smell of teen spirit has remained a metaphor. In this essay, I will attempt to outline how contemporary commercial perfumery serves as a supplement to the audiovisual world of pop music, enhancing and extending the desired images of pop musicians. The notion of performativity plays a crucial role in this connection. I will focus on mainstream pop music, notwithstanding that pop actually is defined as the dialectical interplay of mainstreams and subcultures.

Firstly, I will elaborate on my understanding of pop culture and performativity in general, secondly point out some similarities between the characteristics of pop and perfume, thirdly present and discuss a selection of fragrances produced for contemporary pop music stars such as Justin Bieber and Lady Gaga. I will show that perfume serves as a fort at the edge of the ever expanding pop music frontier, filling the last voids within the immersive hothouse that pop culture has become in the course of the long 20th century.

Gwen Stefani: Harajuku Lovers (Baby), Eau de Parfum

Pop, Performativity, Perfume

This article has a somewhat paradoxical title: »Essence de Pop«. The terms ›pop‹ and ›essence‹ do not go together well. In fact, they lead up to an oxymoron. ›Essence‹ refers to the core substance of an entity, its permanent properties, its unchanging nucleus. Pop culture, however, is a hybrid culture of flux and instability, culminating in postmodernist aesthetics and lifestyles.

In pop theory, pop culture is thus commonly and justly described as non-essentialist, post-essentialist, and performative. Pop is regarded as a culture where the staging, the reinvention of the self as well as the wearing of masks-as-self is the rule rather than the exception. In this connection, pop exemplifies the modern Western transition from a culture of character, i.e. a culture of moral, depth and substance, to a culture of personality, i.e. a culture of mise-en-scènes, invention, re-invention, and performativity. In Greek, ›persona‹ means ›mask‹.

Warren I. Susman has linked the culture of character to the older Puritan tradition and its ideals of self-sacrifice, whereas the culture of personality is linked with the emergence of a marketing-oriented business culture, a »culture of abundance« accompanied by ideals of self-realization around 1900 in the United States of America (Susman 2003: 22, 271-284). This »culture of abundance«, particularly in terms of »constant over-production« (Engell 2004, 192), forms the basic material precondition for the genesis of postmodern pop culture.

Pop as a concept emerged in the 1950s in England on the intersections of art, design, and theory. The members of the London-based Independent Group viewed the products of modern mass culture as artworks in their own right. In their aesthetic practice, they negotiated between popular art, modernism, avant-garde art, and product design, between seriousness and playfulness, anticipating the postmodern principle »Cross the Border, Close the Gap!«, as Leslie A. Fiedler put it in his groundbreaking 1969 »Playboy« article. The British pop art treated seriously what had formerly been denounced as irrelevant for ›high‹ art and culture, not least industrialized methods of production and reproduction.

Accordingly, the canonical figureheads of pop culture have multi-faceted identities and perpetually transform themselves. This is true of masters of the fashion industry and product design as well as the stars of pop music and cinema such as Elvis, Madonna, David Bowie, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Lady Gaga, Jay-Z, or Beyoncé. In the heydays of postmodernism, such public figures represented the self-understanding of the West as opposed to the East, i.e. to the culture and the political systems of the Eastern Bloc: open, democratic, experimental, liberal, playful, yet dead serious in its business mentality.

Since pop is mass-market-oriented, at least in the mainstream, and markets are saturated quickly, constant change is paramount. This is also true of pop subcultures which attempt to distinguish themselves from the mainstream. The ever morphing and disrupting mainstream appropriates and cannibalizes subcultures, thus forcing the subcultures to transform as well.

In short, if there is an essence in pop, it is a paradoxical essence, a non-essential essence, an existentialist essence, as it were: in pop culture, existence precedes essence, notwithstanding the fact that pop culture consists of clearly definable and standardizable ›ingredients‹. The principle of celebrity, namely being famous for being famous, exemplifies the performativity of pop.

Precisely in this connection it is promising to explore the relationships between pop and perfume. I would like to introduce the portmanteau »the perfumative« to approach this relationship, thus highlighting the performative, ephemeral properties of perfume while at the same time characterizing it as a solid cultural symptom. The term »perfumative« stems from Jacques Derridaʼs 1984 lecture and essay »Ulysses Gramophone. Hear Say Yes in Joyce« in which he speaks of the »perfume of discourse«; a discourse that is »close to the inarticulate cry, a preconceptual vocalization« (Derrida 1992: 297). The French poststructuralist philosopher even contemplated turning »this paper into a treatise on perfumes […] and called it ›On the perfumative in Ulysses‹« (ebd.: 300). He furthermore poses the question if »we can sign with a perfume«? (ebd.: 309) Or is perfume rather comparable with a non-descriptive speech act such as the ever-recurrent word »yes« in Joyceʼs novel? Unsurprisingly, Derrida regards »yes« as a genuinely performative word and, in accordance, perfume as genuinely »perfumative«. However, whereas Derrida is concerned with the transcendental dimensions of performativity, I am rather interested in its historico-cultural dimensions with regard to the pop era and the aesthetics of perfume.

The Polish philosopher Zygmunt Bauman has subsumed these dimensions under the term »liquid modernity« and has also used the term »performativity« in this connection: the post-Fordist experience economy of the 20th century, Bauman argues, favors »subjectivity, playfulness and performativity« (Bauman/Lyon 2013: 65). Tellingly, Bauman has also introduced an olfactory metaphor in his essay »The Sweet Scent of Decomposition« (1993).

The »sweet scent of decomposition« refers to the social changes in postmodernity and to the language of Jean Baudrillard, the apocalyptic interpreter of the postmodernist condition. According to Bauman, the vocabulary by which Baudrillard dissects postmodernity is a vocabulary of »touching and sniffing«; a vocabulary that leads »into a world where nose and fingertips, not eyes and ears, are the message«; a vocabulary that conjures up »tactile and olfactory sensations« (Bauman 1993: 23); a vocabulary that makes us »inhale pungent or acid, putrid or balmy, musky or spicy odours« (ebd.: 24). This ›stinking‹, decidedly unscientific vocabulary is then contrasted with Western modernity as Bauman views it, namely as an era that is obsessed with »keeping away the odours of decomposition« by producing a pervasive »thick cloud of deodorizing perfume« (ebd.: 30). Hence both scent/perfume and performativity appear as categories in Baumanʼs writing.

Now, let us again draw a parallel to pop culture. The term ›pop‹ appeared for the first time in the depiction of a cloud hovering above depictions of a sweet soft drink, an erotic pin-up, sweet cherries, and a warplane, namely in 1947 in Eduardo Paolozziʼs collage »I was a rich manʼs plaything«. Paolozzi was a member of the aforementioned Independent Group. Clouds, sweetness, sexyness, but also militant aggression – this combination anticipates Baumanʼs and Baudrillardʼs view of the postmodernist condition. In fact, the »sweetness« of the Western era of decomposition as described by Bauman is irreducibly linked to the consumerist pop culture of constant overproduction – the »culture of abundance« (Susman) – accompanied by the purported boundless possibilities of the performative subject. The San Francisco indie rock band Silver Jews have portrayed this militant sugar-sweet culture in their song »Candy Jail« (2008) as follows: »Life in a candy jail / With peppermint bars / Peanut brittle bunk beds / And marshmallow walls / Where the guards are gracious / And the grounds are grand / And the warden keeps the data on your favorite brands.«

Perfume, in turn, is performative not least with regard to its ephemeral presence and its pervasive quality. This aisthetic-aesthetic quality goes against the grain of the traditional Western differentiation between subject-object, artist-artwork, stage-audience. Perfume is worn as an ephemeral artefact on the body, but its molecules leave the body one after the other and directly impact the sensory system of the recipients; the fragrance mixes with the scents of its medium, i.e. of bodies and of spaces. Perfume connects people physically yet invisibly; it creates spaces of immersive involvement.

In this regard, parallels not only to the neoliberal experience economy and immersive consumer culture, but also to body and performance art are obvious. A strong antiformalist impulse, as outlined by Amelia Jones in her seminal book »Body Art. Performing the Subject« (1998), establishes the covalent bond between perfume, body, and performance art, metaphorically speaking. We can also include large parts of pop culture and pop art here. It is telling that the most prominent solicitor of pop art in specific, as well as of pop culture in general, namely Andy Warhol, sided against the formalist art which the New York School and its court critic, Clement Greenberg, stood for in his day.

Warhol envisioned pop culture as an immersive culture; as a sphere in which art and life, commerce and avant-garde, underground and mainstream mingle. It comes as no surprise, then, that Warhol was an avid collector of perfumes. In his »Philosophy of Andy Warhol« he wrote: »[A] way to take up more space is with perfume. […] I switch perfumes all the time. If Iʼve been wearing one perfume for three months, I force myself to give it up, even if I still feel like wearing it, so whenever I smell it again it will always remind me of those three months. I never go back to wearing it again; it becomes part of my permanent smell collection« (Warhol 1975: 150). Warholʼs »permanent smell collection« consisted of partially emptied, »semi-used« perfume flacons that are today held in the archives of the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh.

In fact, Warholʼs work was all about »taking up more space«, of conquering market after market. Perfume fits in perfectly here. Just like music, perfume fills that spatial void which the reception of paintings, sculptures, prints, or installations presupposes. One cannot walk through solid art objects. But one can walk through music and scent. The latter engulf the recipient and create an ›artmosphere‹, as it were. This brings to mind Antonin Artaudʼs ideas from his pioneering text »Theater of Cruelty« (1938): »We abolish the stage and the auditorium and replace them by a single site, without partition or barrier of any kind, which will become the theater of the action. A direct communication will be re-established between the spectator and the spectacle, between the actor and the spectator, from the fact that the spectator, placed in the middle of the action, is engulfed and physically affected by it« (Artaud 1958: 96). Perfume, I would argue, is predestined as an aesthetic means to achieve these goals.

Warhol was as well concerned with re-establishing a direct communication between art and life – a communication that the pop artists of the 1950s and 1960s believed had vanished in the course of the elitist ›ab-straction‹ of art. The art critic Yves Michaud (2003: 18) goes so far as to claim that along with the general explosion of aesthetics in postmodernity, art has entered »lʼétat gazeux«, i.e. a gaseous state; that it has become »a perfume or jewellery« (»un parfum ou une parure«). This state is the state of »the perfumative«.

Notwithstanding these roughly, yet hopefully somewhat convincingly sketched interrelationships between perfume, performance, performativity/perfumativity, and pop, perfume – and scent/odor in general – plays a minor role in pop theory. While there is a plethora of texts revolving around the role of the body in pop music, these texts hardly ever deal with taste, touch, and smell. The main focus of pop theory has remained on, speaking with David Bowie, »sound and vision«, and thus, of all senses, on the allegedly intellectual, theoretical, and analytical »distance senses«, as Aristotle has called them. It is as if this mode of reception was to compensate for the disturbing easiness of Pop. At least in its beginnings, Pop was a telling name. Short. Simple. Easy to remember. Un-intellectual. Almost a sound word. This was before the union of pop culture and avant-garde was established, arguably around 1965, with sophisticated mass artefacts such as the Beatlesʼ album »Sgt. Pepperʼs Lonely Hearts Club Band« (1967).

Given the blatant lack of scent in pop theory, the German historian Bodo Mrozek has called for an »olfactoric of pop« in 2016. In Mrozekʼs view, scent is a »desodoratum« in the history and theory of pop. He regards perfumes as »media for sensually perceivable aesthetic information of everyday life« and stresses the intersensory aspects of pop music: »We do not only hear with our ears but with the entire body that is capable of perceiving vibrations as tactile information.« Interestingly, recent scientific studies have shown that scent receptors are not only located in the nose. On the contrary, almost every somatic cell has scent receptors. This does not mean that we literally ›smell‹ through our entire body. Yet it is beyond doubt that smell does not only affect the nose, just like sound is perceived not only through the ears. This process of quasi-smelling through the entire body is, to some extent, comparable with the process of seeing: a signal captured by somatic cells in the eye is processed and interpreted by the brain. We do not ›see‹ images. We ›see‹ interpretations of sensory inputs. This makes the understanding of aesthetic perception even more complicated – and the covalent bonds between the multimedia, multisensory pop music genre and perfume even more numerous.

Smells Like Star Spirit. Perfume as an Olfactory Supplement to Fame

When the stars of pop music have reached a certain level of fame and market penetration, they inevitably have to transcend the confines of »sound and vision«. After all, capitalism means growth – »to take up more space«, in Warholʼs words. At some point, sound recordings, concerts, video clips, and interviews no longer suffice to nurture this growth in the pop music business. This is when perfume, among other cosmetic and fashion products, comes into play. Fragrances are developed and thrown on the market to fill the last voids that fame has not yet reached. Perfume is an extension of the audiovisual aura.

If sound and vision are inextricably intertwined in pop music, perfumes can help to reinforce or extend specific multimedia images of pop stars as olfactory supplements. It is salient to stress that in the pop pluriverse, scents and fragrances do not exist on their own, just like pop music is being carried along by waves of images, texts, costumes, performances, etc. The culture of pop music has always been relational, hybrid, multimedia, and multisensory. In this connection, perfume is just one of the many elements that are used to create pop personas, i.e. authentic masks – an element, however, that so far has ranked lowest in the hierarchy of pop, just like scent has traditionally ranked lowest in the hierarchy of senses in Western philosophy. In this regard, pop is pretty old-fashioned.

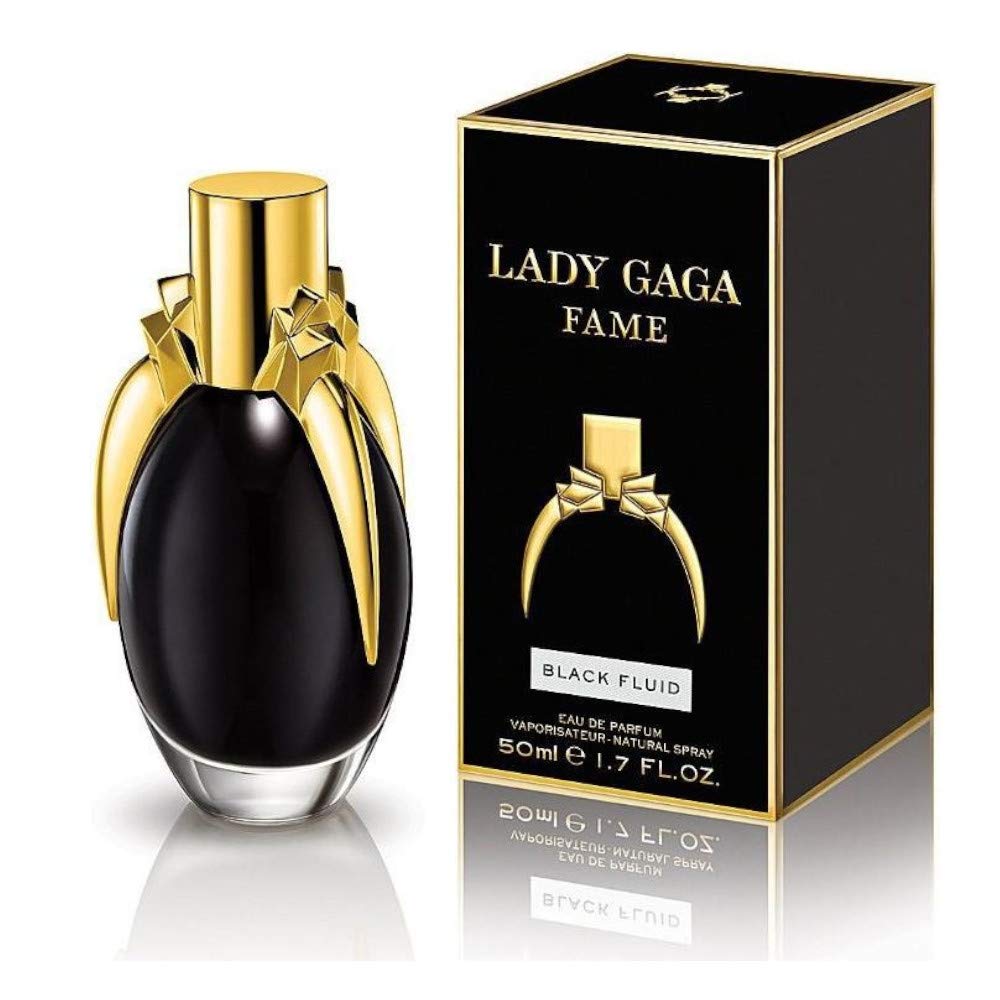

Todayʼs pop stars use fragrances to extend their aura to the very bodies of their fans. Consuming the perfume of a pop star promises a more physical, more intimate encounter with the respective star than the consumption of sound and vision alone. Music is heard. Pictures are seen. Scent is worn on the skin. Mostly pop stars are not directly involved with the physical creation of their fragrances. One could rather compare them with aristocrats who commission a painting from a renowned workshop. In coordination with their consultants, they draft a concept and deliver a set of specifications. The execution is up to the professionals. Usually one of the big international perfumery companies is commissioned to produce a fragrance based on some characteristics the pop stars and their advisers determine in advance. In the case of Lady Gagaʼs »Fame«, for instance, the perfumers Richard Herpin, Honorine Blanc and Nathalie Lorson were entrusted with the task by the multinational Coty.

Since pop star fragrances are intended for the mass market, the result has to be approachable, affordable, and easily digestible, while at the same time radiating an aura of uniqueness, difference, and identity. In 2017, the Canadian singer and songwriter Shawn Mendes said about his first fragrance »Shawn Mendes Signature«: »I wanted to create a scent that all of my fans can relate to and love to wear. I think a really timeless scent doesnʼt have to be overly masculine or feminine – so this felt like the perfect balance.« In the same breath he stressed that he »wanted to do something different and unique. I wanted to make something for all of my fans that really represents the relationship I have with them, and that also fits in line with the authenticity that I strive for when making my music.« (Quoted after Krause 2017)

This is a case in point. In pop, at least in the mainstream, everybody wants the same, but different. Pop products have to be authentic and unique, but also standardized and reproducible. Theodor W. Adorno has famously denounced this characteristic of pop music in particular and »culture industry« in general as »pseudo-individuality«. However, in defense of pop one could argue that pop at least thwarts the ill-fated myth of the »in-dividual«. There is no in-dividuality in pop culture, there is only singularity through similarity. Signature fragrances in pop music such as Mendesʼ perfume speak volumes of this basic pop condition.

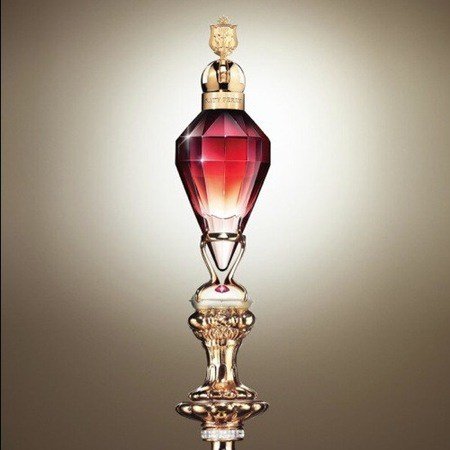

For the preparation of this essay, I have gotten up to my ears in debt to test a number of pop star perfumes: Sean Johnʼs »Eau de Toilette«, Britney Spearʼs »Curious«, Avril Lavigneʼs »Forbidden Rose«, Lady Gagaʼs »Fame«, Justin Bieberʼs »The Key«, Katy Perryʼs »Killer Queen«, KK Downingʼs »Metal for Men«, Gwen Stefaniʼs »Pop Electric Baby«, Beyoncéʼs »Heat Seduction« and Nicki Minajʼs »Minajesty«. In the following, I will discuss a selection of these perfumes exemplarily and situate them in the context of pop and performativity.

Justin Bieberʼs »Key« is flowery, sweet and bubblegumish, clearly intended for his peer group, namely young girls, or rather: for what these girls are imagined and expected to be by marketing departments. The white, column-and-capital like flacon is adorned with a golden key. However, the designers somehow forgot to add a lock that it could open. Luckily, Bieberʼs perfume is accompanied by a short movie that makes clear what perfume and flacon alone fail to express (2013). A summary of the plot reads like this: young girl in luxury hotel wears »The Key«, goes to bed. Justin arrives in luxury car, wakes up young girl. Innocent romantic encounter, girl falls asleep. Justin wakes up another young girl in another hotel room by presenting her a gigantic cake. Sexy romantic encounter, girl falls asleep. Justin moves on to a third hotel room filled with cakes, biscuits, and another girl. Slightly fetishistic romantic encounter. Justin wakes up, realizes: just a dream, smiles naughtily – maybe not just a dream? YouTube user Sharjanét Lewis (2014) has commented the movie as follows: »My interpretation of this video is that every time a girl/Belieber wears or holds ›The Key‹ from the perfume, it allows them to ›Unlock the dream‹ of their ideal dream of Justin Bieber coming to their Hotel door and doing what they fantasise of doing with him.« This seems quite accurate. All in all, the narrative used to support Bieberʼs fragrance stays within the boundaries of the expectations one has about him – love is in the air and a flowery scent anticipates deflowering. However, Bieber is also presented as an ambiguous persona who smoothly switches from innocent romantic to naughty womanizer. There is no stable ›character‹ but a ›personality‹ who uses different strategies to collect different, in this case: romantic and erotic, experiences. Bieberʼs perfume is portrayed as the literal door opener to the literal as well as metaphorical rooms containing these experiences. Once again, Warholʼs one-liner about perfume makes a lot of sense: »[A] way to take up more space is with perfume.«

Nicki Minajʼs »Minajesty«, a perfume for women and probably for the third and xth sexes, is more bubblegumish, fruitier, and poignant than Bieberʼs »The Key«. These qualities are underlined by the sculptural bottle design. The bust-shaped flacon depicts Minaj herself, wearing her trademark pink wig, and thus one of the shriller, commercially queerish – some critics would say: pinkwashed – stars of contemporray pop music. In 2013, Minaj gave some background information about the origins of her fragrance: »I like to sleep with them [i.e. her fragrances] over night to see if they pass the overnight test, cause I think when you get up in the morning you should have like some sort of a, you know, sexy smell to you, and thatʼs like itʼs reminiscent of the night before and itʼs like, you know, girls like that.« Hence Minajʼs fragrance is basically about prolonging sexyness, feeling sexy, being sexy, remaining sexy. Minaj even claims to »sleep with« perfumes, i.e. to have olfactory intercourse, as it were.

As for the flacon design, Minaj has stated that she likes »her products to be very Nicki, you know, I think that thatʼs such a big part of building a brand, you know, like just to have it, have what you do say your name even if it doesnʼt say your name.« This statement brings us right back to the performativity of post-essentialist pop culture and of perfume. As mentioned before, Derrida asked the question »can we sign with a perfume?« and went into long deliberations about the »transcendental condition of all performative dimensions«. Minaj, in turn, argues that you actually can sign with a perfume even when you cannot – you just do it, that is: in the pop business, you do it through a tightly knit network of speech acts, pictorial acts, and sound acts; through a network of presence and representation, of meaning and atmosphere, of showing and knowing. »Have what you do say your name even if it doesnʼt say your name« – thatʼs performativity in a popcultural nutshell. »How to do things with perfume«, freely adapted from John Longshaw Austin, is the bottom line of Minajʼs statement.

Lady Gagaʼs unisex fragrance »Fame« is another great example for the multimedia, multisensory network of pop culture. Letʼs start with the visual side. The ovoid, grenade-shaped flacon is elegant and latently dreadful at the same time. It contains a dark liquid. However, when sprayed on a white fabric, for instance a smelling strip, the color is gone. All that remains is a transparent film. This is an appropriate symbol for what I have written above regarding the non-essential, ephemeral, performative essence of pop culture: what is dark and opaque can become light and transparent or vice versa without changing its substance, just like Lady Gaga is controversial and conformist, punk and entrepreneur, art and pop; just like Bieber can change from innocent romantic teenager to naughty seducer within seconds. Gagaʼs flacon is crowned by a golden cap that reminds of Louise Bourgeoisʼ spider sculptures. This is certainly no coincidence. Gaga has appropriated Bourgeoisʼ spiders on other occasions more directly und unmistakably, for instance when performancing her song »Speechless« in 2009 live at the Royal Variety Performance in Blackpool, England. For this occasion, she had her piano mounted on monstrous, approximately 10-foot tall spider legs. Bourgeois has included perfume in the installation »Cell II« (1991), more precisely bottles of Jacques Guerlainʼs orientalistic fragrance »Shalimar« from 1921. Gaga, in turn, has repeatedly ›orientalized‹ herself, as it were, with Burka-like outfits or traditional Japanese costumes, thus attracting criticism for cultural appropriation.

Gaga carries delight in distinguishing herself from more ›conventional‹ pop stars through, among others, collaborating with performance artist Marina Abramović, borrowing visual elements from the world of fine arts as in the case of »Fame«, or by framing her work as »art pop«. The sophisticated Bourgeois-style perfume cap literally squats the flacon, just like the term »art« squats »pop« in Gagaʼs self-invented »art pop« genre. Probably because ›high‹ art is supposed to be challenging, »Fame« was rumoured to smell of blood and semen before its release in 2012. As far as I can tell, it does not. »Challenging«? Not really.

To learn more about the perception of the pop star perfumes I had bought and tested, I conducted two small, non-representative surveys with seven students and lecturers from the Berne University of Applied Sciences (department conservation and restoration) and 20 students from the Poznań University of the Arts in 2018 (all departments and specializations). Whereas the scent of Britney Spearʼs »Curious« was more or less unanimously considered as »cheap«, »sweet/sugary«, »lilac«, »weak« or »like toilet cleaner« – one said it smelled like »a bunch of sweating young girls in a locker room« –, the reactions to Lady Gagaʼs perfume were quite diverse. The students from both universities described it as »heavy«, »dark«, »interesting«, »very sweetish«, »tart«, »cherry blossom«, »light«, »powdery«, and »neutral«. At least in these playful surveys, Lady Gaga has succeeded in closing up to the ambivalence und unpredictability of modernist and avant-garde arts under the umbrella of pop culture.

Let us end with yet another ambiguous pop star perfume, the less well known »Metal for Men«, developed by The Astbury Fragrances for KK Downing, the former guitarist of Judas Priest. Surprisingly, the scent is not dark, pungent, and musky, as one could expect from a metal fragrance. It is fresh, bright, heavily lemon. The cap of the flacon resembles an anvil, yet it is made of transparent plastic – again: surprisingly. After all, literal metal is anything but transparent. On the one hand, a conventional symbol of metal culture is used, namely the usually solid, heavy, dark anvil, whereas on the other hand the symbol is turned against itself, as it were, by presenting it as light, transparent, and fragile.

Against the backdrop of Judas Priestʼs hitherto work, this ambiguity makes sense. The British band has always played with ambiguity and excelled in keeping their options open, starting out as a bluesy hardrock band and adopting the metal image only in the late 1970s. In the 1980s they made use of the latest sound technologies such as guitar synthesizers while retaining classical metal elements. In the 1990s it became obvious, after singer Rob Halfordʼs outing as gay, that the band had long incorporated elements from gay leather fetish subculture in their allegedly macho-masculinist visual image.

»Metal for Men« has a dialectical quality with regard to the ›metal bodies‹ it is targeted at: already in its beginnings, heavy metal was ›old‹, i.e. morbid, obsessed with decay and death. Hence a little lemon is a welcome distraction – a distraction that at the same time reinforces the morbidity of metal dialectically, by means of contrast.

Summary

I have portrayed postmodern pop culture as post-essentialist, performative, fluid, pervasive, multimedia, and multisensory. Pop culture mirrors the marketing-oriented »culture of personality« as opposed to the production-oriented »culture of character« (Susman). I have then pointed out that scent and perfume appear as significant metaphors in the context of »liquid modernity« (Bauman) and in the context of performative speech acts (Derrida). Perfume can be regarded as the perfect instrument for »taking up more space«, as Andy Warhol put it, literally as well as metaphorically, but also for creating an a(r)tmosphere of constant flux where the acts of grasping and preserving are made difficult. Perfume supplements the performative and immersive project of postmodern pop culture considered as an all-encompassing aesthetic environment, as a global ›cloud‹ that immerses each and every consumer.

In this regard, it is significant that the term ›pop‹ firstly emerged in the depiction of a cloud hovering above images of sweetness and eroticism, as well as of military aggression in a collage by Eduardo Paolozzi. When in pop business markets are saturated, perfume conquers new territories, it »takes up more space«, it pushes the frontiers. As for the pop starsʼ fragrances, the ones by Nicki Minaj and Lady Gaga show the strongest characteristics of »the perfumative«. These perfumes are created for and marketed at ambiguous, flexible, fluid, gaseous, versatile subjects. Yet also Downings »Metal for Men« appeals to more fluid and complex identities than the general audience would usually expect from the heavy metal genre.

In general, pop star fragrances serve as olfactory supplements to performative pop personas created by audiovisual means. They are symbolic forms – formless forms, as it were – of an era of »decomposition«; an era that is arguably still in full swing despite ubiquitous attempts to bring back the essences and identities of the good old days before the rise of the performative culture of personality.

Literature

Artaud, Antonin (1958): The Theater and Its Double, New York.

Bauman, Zygmunt (1993): The Sweet Scent of Decomposition, in: Chris Rojek/Bryan S. Turner (eds.): Forget Baudrillard?, London/New York, p. 22-46.

Bauman, Zygmunt/Lyon, David (2013): Liquid Surveillance. A Conversation, Cambridge and Malden.

Derrida, Jacques (1992): Ulysses Gramophone. Hear Say Yes in Joyce, in: Derek Attridge (ed.): Jacques Derrida. Acts of Literature, New York, p. 253-309.

Engell, Lorenz (2004): TV-Pop, in: Walter Grasskamp/Michaela Krützen/Stephan Schmitt (eds.): Was ist Pop? Zehn Versuche, Frankfurt a.M.

Jones, Amelia (1998): Body Art. Performing the Subject, Minneapolis.

Krause, Katie (2017): Exclusive: Behind The Scenes of Shawn Mendesʼ ›Real and Organic‹ First Fragrance Campaign, in: https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/exclusive-behind-scenes-shawn-mendes-133000933.html [26.6.2019].

Lewis, Sharjanét (2014), YouTube comment, in: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpDoO84IPTc&lc=UggW4FK7UaBzb3gCoAEC [26.6.2019]

Michaud, Yves (2003): LʼArt à lʼÉtat Gazeux. Essai sur le triomphe de Iʼ esthétique, Paris.

Minaj, Nicki (2013): Nicki Minaj Talks New Fragrance Minajesty, in: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=21DVgJVy5Os [26.6.2019].

Mrozek, Bodo (2016): Eine Seife namens Elvis. Plädoyer für eine Olfaktorik des Pop, in: https://pophistory.hypotheses.org/2336 [26.6.2019].

Silver Jews (2008): Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, Chicago.

Susman, Warren I. (2003): Culture as History. The Transformation of American Society in the Twentieth Century, Washington/London.

Warhol, Andy (1975): The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again), Orlando/Austin/New York/San Diego/Toronto/London.