AI Will Reward Us When it Reigns

One conspiracy theory has it that every time the protons in CERN’s Large Hadron Collider clash—that’s about a billion times a second—one of an infinite number of possible future universes is destroyed. Since it was turned on in 2008, the LHC has therefore been burning through reams and reams of the more statistically probable universes, causing the universe we exist in to branch off to more and more improbable, absurd and ludicrous timelines as the years go by. Readers from many years into the future should take note here: this theory, even if you don’t take it literally, brilliantly describes the experience of the years leading up to 2020. Bizarre political upsets, cultural confluences too weird for fiction, countless lightning bolts of disaster big, small and huge, and an increasing, ominous atmosphere of escalation. Not progress, per se, but a helplessly, exponentially building momentum towards a future that is surreal at best, and apocalyptic at worst.

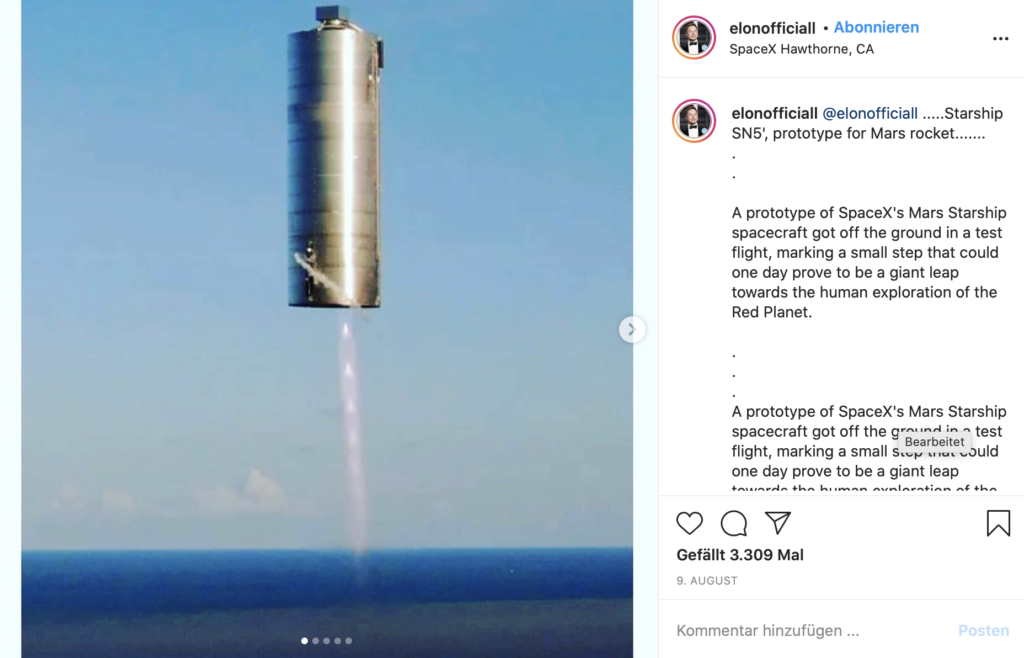

It’s the sort of idea that Elon Musk might believe. Well specifically, Musk, the multi-billionaire CEO of both Palo Alto electric car company Tesla and private spacefaring outfit SpaceX (bringing humans to the International Space Station as of June 2020), believes that this universe is in all probability a simulation, given the likelihood of such powerful simulations being built—and indeed, nesting inside each other—over the lifetime of the cosmos.

Few figures have so embodied the age as Elon Musk, and I don’t mean that in the way that Musk’s legions of fans think of him: as a heroic, thrusting future-builder in the tradition of James Watt and his industrial revolution, Isambard Kingdom Brunel and mass transportation, Thomas Edison’s media and electricity, or, with embarrassing regularity, the fictional Tony Stark, who built his own hi-tech suit and became the superhero Iron Man. No, Elon Musk embodies the age because he so succinctly exemplifies the chaotic multiplicities through which dreams and reality, the sublime and the ridiculous, and great power and great irresponsibility, have all been colliding repeatedly, billions of times a second. At the start of the decade, Musk seemed an exciting personification of a better tomorrow. Billions and billions of seconds later, he unveiled the Tesla Cybertruck in November 2019, an angular monster that seemed designed to bring a 1980s videogame avatar into the world of today’s awesome grown-ups. As the Cybertruck hunkered onstage in front of the world’s media and an enormous online audience, Musk ordered the truck’s Chief of Design to throw a fist-sized metal ball at the supposedly indestructible glass windows. ‘Oh my fucking God,’ Musk exclaimed as the ball made a giant circular crack in the driver’s window. It was just the latest of countless moments of clownery in the entrepreneur’s public relations. He had been sued for defamation after he responded to a diver’s criticism of Musk’s hi-tech plans to rescue the soccer team trapped in a cave in Thailand by calling him a ‘pedo guy’ on Twitter. And he had also been sued for announcing he would take the company private after the shares reached $420, a number he picked because of its marijuana symbolism and because he thought his girlfriend ‘would find it funny.’

This girlfriend is the indie popstar Grimes, now the mother of their child—her journey through the 2010s has also been one of multiplying strangeness. I first saw Grimes’s face in 2011, peering eccentrically out from the cover of Darkbloom, her split EP with singer and synth-player d’Eon. This was effectively Grimes’s debut, with her previous two albums having not seen much attention beyond her home DIY scene in Canada. With Grimes and d’Eon swaddled in furs and foliage, staring nervously yet defiantly at the viewer, Darkbloom’s cover seemed to represent the wild weirdos north of the American border coming in from the cold obscurity. The first track ‘Vanessa’ was an instant hipster hit, its bouncing ballet-class earworm and twee art school video, both somewhat indebted to Lykke Li, fitting perfectly into the indie aesthetics of the time. Grimes’s distinctive singing style echoed and even surpassed those of Li, CocoRosie and Joanna Newsom in childlike sweetness, part of a tradition going back to the 1980s in which the political stance of indie music—its critique of modernity, rationalism and commercialism—found symbolic expression in innocence, spontaneity and imperfection. Nearly a decade later, Grimes has embraced modernity, and her celebrity is becoming comparable to that of Björk in the 1990s. In Summer 2018 I saw that she had become a giant, mesmerized by her laptop screen in a billboard over the streets of New York, as part of Apple’s Behind the Mac campaign. Her child with Musk arrived in May 2020, and was named ‘X Æ A-Xii.’ ‘X,’ she explained, is the unknowable variable, Æ is Grimes’s ‘elven spelling’ of AI, and ‘A-Xii’ is the model number of a supersonic aeroplane she and Musk admire.

A few months earlier, Grimes had released her fifth album, Miss Anthropocene. Much of it is a darkly ironic conjuring of posthuman dystopia, its name a combination of ‘misanthropy’ and ‘Anthropocene,’ the term for the geological age marked by human activity that has lately seen much discussion in the arts and humanities. In places, the album appears to applaud or encourage the subjection of humanity and the planet by powerful technologies.

As such, it takes on an aesthetics of ‘accelerationism,’ which names the tendency to want to accept and, typically, drive further the destructive and dehumanising proclivities of capitalism and/or technological advancement, either as some form of political strategy or for its sheer horrific thrill. It is a tendency that was noted in the philosophical writings of Lyotard, Deleuze & Guattari, and associated with the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit at Warwick University in the UK in the 1990s. Benjamin Noys’s excellent book Malign Velocities, also finds resonances between accelerationism and cyberpunk literature, and in music in techno and its surrounding imagery and narratives. Grimes is hardly the first musical accelerationist, even in the rough decade that the concept has been discussed in the arts. One of the few generalisations that can be made about indie music in the 2010s is that the era saw an embrace of electronics and computerization both in the production of the music and in the stories it told. If the results were often disturbing, this was perhaps part of the point, and artists like James Ferraro, Holly Herndon and Arca came to explore this new sensibility with varying hues of critique and irony.

Compare ‘Vanessa’ with one of the singles from Miss Anthropocene, ‘We Appreciate Power,’ and the shift towards the sounds and stories of traditional humanity crushing under the heel of its hi-tech future is immediately obvious. Punctuated by screams and steam hammers striking anvils, the song prompted comparisons to industrial and nu metal, and its moaning, distorted guitars loudly connoting the roaring machine as part of the long tradition of dehumanising noise stretching back at least to Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music. According to its press release, the song ‘is written from the perspective of a pro-AI girl group propaganda machine who use song, dance, sex and fashion to spread goodwill towards Artificial Intelligence (it’s coming whether you want it or not).’ Hence the lyrics of verse two:

People like to say that we’re insane

But AI will reward us when it reigns

Pledge allegiance to the world’s most powerful computer

Simulation: it’s the future

Its chorus, sung by American musician HANA:

What will it take to make you capitulate?

We appreciate power

We appreciate power

The song works as a response to a notorious thought experiment known as Roko’s Basilisk, which proposes that a future all-powerful artificial intelligence could exact retroactive revenge on those of us who did not actively work to bring about its existence. One addendum to the notion is that we might currently be living in a simulation which the AI is running in order to decide who is to be judged. Thus ‘We Appreciate Power’ is Grimes and HANA’s effort to pre-emptively ally themselves with the future AI. Grimes and Musk have been public about the role that the Basilisk has played in sparking their relationship. Googling a pun he was about to make, Musk found that ‘Rococo Basilisk’ was already a character Grimes portrayed in the video for her song ‘Flesh Without Blood,’ and got in touch. Musk has warned of the danger he perceives in developing artificial intelligence, putting it ahead of nuclear weapons on the list of future threats to the human race.

‘We Appreciate Power’ is not the only place on Miss Anthropocene in which the demise of humanity is apparently hastened. On ‘Violence’ Grimes’s lyrics eagerly submit to sadism told over chugging synthwave-trance hybrid that could have been the soundtrack to a promotional video for a set of luxury condominiums with a frictionless yet cramped lobby of liquid crystal displays: ‘You wanna make me bad, make me bad, and I like it like that’. Grimes has provided additional context to the song, identifying its voice with the planet Earth in the throes of an abusive relationship with the humans that are destroying it. On the same kick, another of the album’s singles, ‘My Name is Dark,’ features the lyric ‘imminent annihilation sounds so dope.’ Most succinctly, advertising for Miss Anthropocene involved billboards that proclaimed ‘GLOBAL WARMING IS GOOD.’

The irony of such gestures, blunt though it is, is at least made apparent elsewhere on the album. ‘Before the Fever’ is instructive:

This is the sound of the end of the world

Dance me to the end of the night, be my girl

Madness, intellect, audacity

Truth and the lack thereof

They will kill us, oh have no doubt

But is it enough merely to signal irony? While the wink on ‘We Appreciate Power’ might be subtle enough to cause third-degree burns at thirty kilometres, the allegiance she pledged to the world’s most powerful computer in the real world is less easily sterilized. Apple are driving neocolonialism in Africa, suicide-inducing working conditions in China, and an appetite for planned obsolescence and unrepairable commodities throughout the developed world. With Musk at her side, Grimes seems to dare her audience to ask whether, like so many artists before her, her real life echoes her music, in this case its wry accelerationism. Of course the cyberpunk princess would be dating the billionaire prince of technocapitalism—it’s comic books come to life! Less magical was the time reassured her Twitter followers that Musk had never prevented Tesla workers from unionizing and that fears to the contrary are ‘literally fake news,’ or her tweets defending Musk’s donations to the Republican party as ‘the price of doing business in America.’

These reactions raise the possibility that for all its fantastical hyperreality, Grimes’s artfully ambiguous capitulation to the Machine looks more like a depressing, deflationary form of realism when the costumes are back on the hangar. Worse still, all the irony provides an alibi: Grimes couldn’t be part of the problem, she seems to suggest, when she has so clearly painted the problem in a cartoonishly evil light. But rather than directing us away from the evil, the thin veil only affirms the oncoming dystopia even more crushingly. It is difficult to appreciate the dangerous thrill of accelerationist aesthetics, even as a form of honesty to the experience of modernity’s turmoil, affective temptations and moral dilemmas, when a billionaire CEO is agitating for his car factory to reopen in the midst of a deadly pandemic—as if a clearer illustration of the death-drive foisted upon today’s working cyborgs were needed. Or when said billionaire associated himself with alt-right imagery by cryptically encouraging Twitter followers to ‘take the red pill,’ the motif from cyberpunk film The Matrix that has been adopted by angry forum-posters to represent the newfound consciousness that feminism is a conspiracy against them. Or when Ivanka Trump responded that she had already taken it.

When the Large Hadron Collider was turned on, innocence of modernity was the dominant orientation of indie music. Reality soon became so warped that in order to continue to tell the truth, it had to reverse course and make a pact with the technologies and mediations that embody today’s increasingly sublime vectors of power. Yet while today’s world has its strange spectacles—the indie heroine on the red carpet next to the billionaire—they are not simulations, not fantastical images from the future. They are material realities, ones that were always possible. Tomorrow will be real, too.

[In deutscher Übersetzung ist dieser Beitrag in Heft 17 von “Pop. Kultur und Kritik” erschienen.]