Peaches, Amanda Palmer, PJ Harvey u.a.

Introduction:

The ambiguous relationship between women’s popular music and feminism

There appears to be a discrepancy between female artists in the music industry and popular culture, and the women and men who write about these artists and reflect upon the latter’s creations. Popular female artists often do not like to be associated with »the F-word« (McClary 2000: 1284); being labeled as a feminist is seen as stigmatic because of the many negative associations attached to feminism.

Yet, there are female pop artists out there that are reacting against the double standards women have to deal with, and that hence could be seen as feminists. Just recall Pink’s »Stupid Girls« video, in which she reclaimed female sexuality by criticizing America’s antifeminist celebrity culture (Pink 2006).1

Although »Stupid Girls« was not that well-received in some feminist circles because of its mocking undertone – women that label other women as stupid borders on exploitation, obviously – it in the end gave us a positive message of female empowerment. And the same could be said about the hits »PU$$Y« and »212«, respectively written by Australian-American rapper Iggy Azalea and Harlem rap sensation Azealia Banks, in which both artists touch upon female pleasure and sexuality in an empowered manner (Azalea 2011; Banks 2012).

So, at least a part of today’s popular music created by women could be situated in the feminist political domain of fighting for gender equality, equal sexual rights and the freedom of female expression, if it were not for these artists themselves, who are usually wary of being branded as feminists. The aforementioned artists, for instance, have never called themselves feminists, and other American artists, such as hip hop sensation Nicki Minaj and pop icon Lady Gaga, aren’t exactly feminist-friendly either: whereas Minaj on occasions refers to girl power – a cuter version of feminism – Gaga once explicitly stated that she is »not a feminist,« »hail[s] men,« and »celebrate[s] American male culture« (Lady Gaga and Lydverket 2009).

This ambiguous, fuzzy relationship between women’s music2 and feminist thought and practice surely is shocking: are we as feminist cultural theorists, pop culture aficionado’s and music journalists then basically reading our own interpretations into these cultural artifacts? And, if so, does the category of feminist-inspired women’s music even exist?

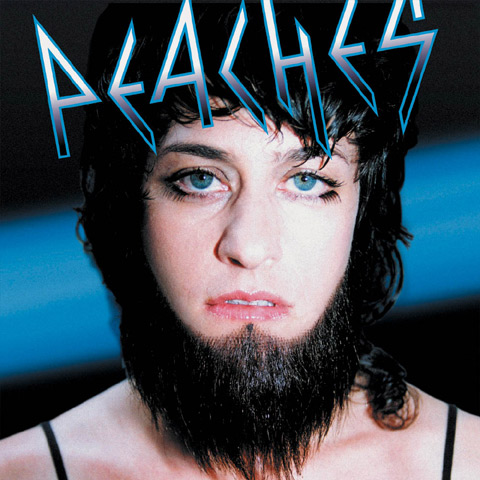

I will engage with these questions by close-reading some of the lyrics and performances by female artists in today’s mainstream and alternative music scene via a reader-based approach (also see e.g. Burns/Lafrance 2002). I have chosen five different oeuvres of popular female artists, namely the works of Lady Gaga (Stefani Germanotta), Nicki Minaj (Onika Tanya Maraj), the Canadian queen of electro clash, Peaches (Merrill Nisker), indie icon Amanda Palmer, and British alternative rock artist PJ Harvey (Polly Jean Harvey).

These artists’ oeuvres and the ways they represent themselves differ greatly, but I am drawn to them because all of these artists embody something special: all five of them namely play with contemporary norms of femininity, beauty, and sexuality – acts that could potentially be subversive and feminist. Yet – and this is where my personal attachments to feminism as a political project enter the picture – not all of these oeuvres should obviously be labeled as politically feminist. Although I do not want to make the mistake of putting these oeuvres against one another in a binary manner, and wish to refrain from reinstating feminism as a hierarchical project, I am nonetheless forced to take a stance on the feminist potential in each of these oeuvres.

I will do so by referring to some of these artists as singing sirens, after having analyzed their oeuvres through the strategic essentialist lens of Belgian-born feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray. This article thus combines a reader-based cultural analysis approach with a feminist philosophical strategy, so as to unravel the hidden feminist gems in the oeuvres of popular female artists that have not explicitly labeled themselves as feminists.

But for now, I would like to focus on two striking issues in contemporary women’s music that should be problematized when seen through a feminist lens, namely the hypersexualized and hyperfeminized representation of female artists, and the remarkable references to hysteria.

Hyperfeminization and hypersexualization in women’s popular music:

From Barbie dolls to Gaga feminism

The hypersexualization of women in music and pop culture is not all novel, but what is new is that a lot of female artists nowadays overtly take on these images of sexual excessiveness. Are they by doing so reproducing patriarchy’s ideas about women as Barbie dolls and seductresses, or are these artists deconstructing these stereotypes in a playful and hopefully also feminist manner? Nicki Minaj and Lady Gaga are two exemplary American artists that play with these images in an over-the-top manner, and hence appear to be making potentially feminist statements about female independency, beauty norms and female sexuality.

Nicki Minaj quickly transitioned from being an East Coast underground rapper to a hip hop star during the release of her debut album »Pink Friday« (2010). This transition had an obvious influence on Minaj’s appearance: from then onwards, Minaj presented herself as a Harajuku Barbie doll by wearing pastel colored wigs and skimpy, Japanese outfits. By dolling herself up in such a hyperfeminized manner, one could assume – as many feminists have done – that Minaj obeys to the male gaze (see e.g. Whitney 2012).

If a female artist conforms to such an unreachable ideal of femininity, how could we then still label her oeuvre as feminist? But Minaj in fact remains partially untouched by this critique, since she, as woman from mixed Indian and Afro-Trinidadian descent, challenges hyperfemininity – an ideal that until recently was only considered to be the norm for white, privileged women – and this can be seen when taking a look at the cover of »Pink Friday«.

The album cover shows Minaj as a plastic Barbie with pink hair, yet her arms appear to have been cut off, whilst her legs have been disproportionally elongated. Barbie’s hyperperfect, all-white body is literally being deconstructed here, and this backs up the assumption that Minaj’s image should be read as the opposite of gender-conforming.

But what about Minaj’s lyrical self-representation on »Pink Friday«? Are her lyrics equally destabilizing? »Dear Old Nicki« sets the overall tone of the album: this incredibly self-reflexive song features Minaj, who is talking to her former, more underground self, whilst wondering if she has changed throughout her career (»Yo, did I chase the glitz and glamour, money, fame and power?«) (Minaj 2010). This self-reflexive attitude is also present on »I’m The Best«, in which Minaj claims to have found independency through rapping. Minaj here establishes herself as a self-made woman and a source of inspiration for young girls and women. Yet, the feminist potential of Minaj is, alas, at the same time undermined by misogynist diss tracks such as »Roman’s Revenge« and »Did It On ‘Em«. So, although Minaj at least subverts some of society’s racial and gender norms by challenging a very stereotypical image of white femininity, she also falls into the trap of abusing her power as a woman that has successfully broken through hip hop’s glass ceiling by downplaying the value of other women in the game.

It thus seems nearly impossible to read Minaj’s oeuvre in an unambiguous feminist manner, and we end up in the same tricky situation when examining that other pop icon of the moment, Lady Gaga. Although Gaga has been embraced by the gay community for her LGTBQI-activism, and even though queer philosopher J. Jack Halberstam coined the concept of Gaga feminism in her honor (Halberstam 2012), one could still question whether her oeuvre is feminist in a political sense.

It is true that Gaga »toys with [the] conventional rules of attractiveness« (Williams 2010). Gaga indeed has tackled almost every female stereotype out there. She for instance attacked the binary imagery of the female subject as a nun/whore by dressing up as a dominatrix-like nun in »Alejandro« (Lady Gaga 2009). And she successfully destabilized the whorish connotations that are attached to the Maria Magdalene character she plays in the video for »Judas« by transforming her into a tough biker chick (Lady Gaga 2011).

Gaga as a dominatrix/nun and Maria Magdalene in »Alejandro«.

Gaga as a dominatrix/nun and Maria Magdalene in »Alejandro«.

Pictures taken from the music video by Lady Gaga performing Alejandro.

Gaga as a dominatrix/nun and Maria Magdalene in »Judas«.

Gaga as a dominatrix/nun and Maria Magdalene in »Judas«.

Pictures taken from the music video by Lady Gaga performing Judas. (C) 2011 Interscope Records

Gaga takes the disruption of stereotypical femininity so far that she challenges the Western cultural norms of female sexuality and sexiness as a whole. Or as she once stated: »I just don’t have the same ideas about sexuality that I want to portray. I have a very specific aesthetic – androgyny.« (Lady Gaga in Williams 2010).

The problem with Gaga, however, is that she does not always look that androgynous, or constantly wears a meat costume to address the exploitation of women-as-objects. It is actually pretty ironic that she tries to break away from the cultural ideal of femininity, but then at the same time allows her entourage to dress her up as a passive, sexualized object in videos such as »Poker Face« and »LoveGame« (Lady Gaga 2008).

The ambiguity concerning Gaga’s feminism has been picked up by many feminist theorists: philosopher Nancy Bauer, for instance, has applauded Gaga for making us understand that »being a woman is a matter of artifice, of artful self-presentation«, yet Bauer also claimed that even Gaga cannot shake off the »acts of self-objectification« in a world where women have interiorized oppressive beauty norms (Bauer 2010). Even Camille Paglia – the self-proclaimed maverick of feminism – had her say about Gaga: according to Paglia, Gaga is »so calculated and artificial, so clinical and strangely antiseptic, [and] so stripped of genuine eroticism« that she symbolizes the end of sex itself, rather than being a feminist emblem of female sexuality (Paglia 2010).

Paglia might be going too far here, yet, what is obvious is that Gaga’s feminism turns out to be even more ambiguous or even non-feminist than initially expected: Gaga’s own affiliation with feminist politics is rather vague, and one could obviously also question the potential feminist value of a practice that proclaims that women can become empowered by deliberately presenting themselves as sexual objects. This all tells us that the combination of popular women’s music and feminism is not that evident at all, and aside from the hypersexualization of these female artists, there is another stereotype that has gotten a lot of attention in women’s music lately, and that is the phenomenon of female hysteria.3

Female hysterics in popular women’s music: Female artists going gaga

Hysteria appears to be hotter than ever in popular music. A lot of pop artists are currently experimenting with the imagery of the hysterical, out-of-control woman in their video clips, and this is surprising, considering the fact that in clinical psychology, hysteria has long been replaced with the more gender-neutral pathology of conversion disorder. Hysteria hence is an outdated phenomenon that was said to be a widespread disease during the Victorian patriarchal era – an era in which it was discursively constructed as an exclusively female pathology.4 Hysteria has always been feminized as a disease, and it consequently served patriarchy as a tool of female pathologization and oppression.

So, precisely because of the patriarchal connotations attached to hysteria, it is fascinating to see that both Minaj and Gaga have taken up such a stereotype in their videos: Minaj’s Barbie alter ego, for example, had a cameo in Ludacris’ »My Chick Bad« video, in which she raps the lyrics »the mental asylum [is] looking for me«, whilst lying on a shrink’s couch, dressed in a fashionable straitjacket (Ludacris 2010). This appearance of the hysteric is rather unsettling, because hysteria is used as a gimmick here, without any potentially empowering connotations.

Lady Gaga’s »Marry The Night« video, on the other hand, deals with hysteria in a less shallow manner (Lady Gaga 2011). The video addresses Gaga’s breakdown after her first record label dropped her, and how she overcame everything by transforming herself into the pop icon we know today. The video’s first two sequences are the most fascinating: during the opening scene, Gaga is shown ranting about reality and fiction, whilst being transported on a hospital bed. She ends up in an asylum ward, and after asking the nurse to put on some music, she recalls her past life experiences, whilst the other female patients break out in hysterical laughter. During the next flashback sequence, we are then all of the sudden confronted with Gaga mentally breaking down in her apparent after being rejected by her record label. We see a naked Gaga completely crashing and making wild gestures, whilst covering herself in Cheerios without almost uttering a word.

Gaga going gaga in »Marry The Night«.

Gaga going gaga in »Marry The Night«.

Pictures taken from the music video by Lady Gaga performing Marry The Night (Official Video). © 2011 Interscope

Although Gaga seems to be cathartically reliving her life as a ballerina, one could also argue that she is taking on the image of the female hysteric by portraying herself as an emotionally unstable and muted woman. Both the former and the latter appropriations of hysteria in the end border on exploitation, however: Minaj and Gaga oversexualize the hysterical woman, instead of critically addressing the clichés that have helped spread this stereotypical image.

And that is why I intend to take a different route with this article: instead of analyzing the works of female pop artists that toy with the stereotypes of hypersexualized and hysterical women, but do not take it further than that, I will now try to illustrate how hysteria and other female stereotypes have been dealt with more subversively by Peaches, Amanda Palmer, and PJ Harvey, whom I will call singing sirens.

Why sirens? Female sirens are mythical creatures that have already been described in ancient Greek sagas as seductive, singing creatures. They appear to be connected to the hysteric in a way, since, seen from an Irigarayian perspective, both the female hysteric (see e.g. Irigaray 1977/1985b) and the siren prefigure a female, bodily-expressed language. What appears to be going on in the oeuvres of the above singers, is that they seem to react against the patriarchal construction of hysteria as a female disease (and the hypersexualization of women that goes along with it) through singing. As singing sirens, they take on the image of the female hysteric, but then, unlike Minaj and Gaga, also (partially) transform its essence.

In what follows, I examine how these three artists engage in what I call singing hysterically, or »chanter hystérique«, evaluate whether they are moving beyond solely copying the stereotypical image of the hysteric, and see if we can label them as political feminists. Before doing so, however, I will explain why these artists can be seen as singing sirens by taking a look at Irigaray’s feminist philosophy.

Luce Irigaray’s feminine and feminist philosophy:

Strategically miming and deconstructing the stereotypical image of the hysteric

Luce Irigaray works within the Western traditions of philosophy and psychoanalysis, yet, she is also known for being extremely critical of these discourses: her oeuvre revolves around revealing the phallogocentric logic5 behind the latter systems of thought. Together with philosophers Hélène Cixous and Julia Kristeva, Irigaray is part of the French women’s writing or »écriture féminine« movement, which means that she wishes to (re)create a female Imaginary, or a feminized version of the Lacanian Imaginary, so that women could become speaking subjects of their own – something that had previously been impossible for women in Lacanian psychoanalytical theory.

Next to that, Irigaray has also given special attention to the deconstruction of the masculine-biased image of the female hysteric: Irigaray not only sees the hysteric as a protofeminist in »This sex which is not one« (1977/1985b), but also uses hysteria as a methodological tool in »Speculum of the other woman« (1974/1985a). Irigaray’s thought-provoking »philosophie féminine« has not always been applauded, however: many feminist theorists criticized Irigaray for falling back into essentialism, or the idea that women have specific, unalterable characteristics that are biological instead of socially constructed (see e.g. Plaza 1980).

Irigaray in her works indeed constantly refers to the female sex, which makes sense, since the Anglo-American concept of gender now used to denote one’s socially constructed gender identity, was not a known concept in France at that time. And Irigaray also uses symbols that look suspiciously biologically determining. When speaking about the »two lips« and woman’s sexual plurality that breaks out of »the dominant phallic economy« (Irigaray 1977/1985b: 24), Irigaray seemingly links women to their anatomical constitution. But this construction of female sexuality as something plural is actually part of her strategic essentialist tactic – which differs from traditional essentialist views because it is meant as a political strategy.

This strategic essentialist position has to be understood along the following lines: according to Irigaray, women are excluded from the discourses of philosophy and psychoanalysis, because only men can become speaking subjects there, by identifying themselves with the Lacanian masculine Imaginary that is constructed around the symbol of the Phallus. Irigaray could hence either stay silent, or talk like a male philosopher. But both options are not exactly productive, if one is looking for a way to criticize phallocentric discourses. There is another, rather tricky way to speak – and speak up – as a woman, though: according to Irigaray, »woman does not have access to language, except through recourse to ›masculine‹ systems of representation« (ibid.: 85).

So, if one dares to take on the stereotypical feminine role that patriarchy ascribes to women, then one might be able to speak as a woman – a woman that is nonetheless still stuck in the patriarchal system. And this is exactly what Irigaray does in her philosophy: she mimes the stereotypical image of woman, and hopes to do more than purely reproduce this stereotype. Because Irigaray wishes to deconstruct phallogocentric thought by »jamming the theoretical machinery itself« (ibid.: 78), it is obvious that she is not naively going to repeat female stereotypes. Irigaray’s mimesis is in fact reproductive – as in repeating woman’s place in patriarchy – and productive – as in going beyond these patriarchal meanings. When taking on the role of woman in phallogocentrism, Irigaray hence tries to disrupt the stereotypical definition of woman:

To play with mimesis is thus, for a woman, to try to recover the place of exploitation by discourse, without allowing herself to be simply reduced to it. (ibid.: 76)

Irigaray’s essentialism should thus be seen as strategic, and what is fascinating, is that she actually reappropriates the stereotypical image of the female hysteric. The hysteric has always revolted against patriarchal suppression, in Irigaray’s eyes, because she refused to be muted. Since the hysteric does not have access to a language of her own, she mimes and playfully disrupts masculine language through her excessive, physical gestures. The hysterical woman thus »speaks in the mode of a paralyzed gestural faculty« (ibid.: 136).

The hysteric hence is a protofeminist, since she shows us that there is a disruptive feminine energy or excess that has not yet been infected by phallogocentrism. Seen through an Irigarayian perspective, the female subject is much more than the roles patriarchy gave to her: she might have been muted and objectified, yet, the hysteric seems to know that the reason why »women are such good mimics« has to with the fact that »they are not simply resorbed in this function« (ibid.: 76). Women »also remain elsewhere«, and the female hysteric reveals this »elsewhere«; an »elsewhere« that according to Irigaray, points at a feminine protolanguage and a potential feminine Imaginary (op. cit.).

Irigaray then also engages in a hysterical miming of her own in her works, and this is where the concepts of strategic essentialism and »chanter hystérique« come back into the picture. Irigaray namely uses the hysteric’s mimicking as a textual methodology in »Speculum«: she there hysterically rereads philosophical and psychoanalytical authors so as to reveal, mime, and then ultimately deconstruct their faulty representations of women.

This hysterical rereading is strategic and political of nature: Irigaray obviously runs the risk of falling back into reproducing the phallic stereotype of the female hysteric, but she really does more than simply play with the essentialist image of female hysteria. Irigaray sees the female hysteric as a rebel and revolutionary: the hysteric opens up the long-forgotten domain of the female Imaginary that provides us with untainted images of femininity, such as the two lips, a symbol that Irigaray puts to use in her own philosophy.

The hysteric hence brings Irigaray the material to support her project of speaking (as) woman, or »parler femme« and writing (as) woman, a feminine language that is strongly connected to »the gestural code of women’s bodies«, and that is anticipated by the hysteric’s gestures (ibid.: 134). This project of »parler femme« again is intended to be political: »by speaking (as) woman, one may attempt to provide a place for the ›other‹ as feminine« (ibid.: 135).

So, by revaluing the female hysteric, and by challenging this stereotype, Irigaray disrupts the systems of phallogocentrism and patriarchy that have hystericized and objectified women for decades. Irigaray wants to make room for a new, or rather previously repressed, female Imaginary and language, so that women could finally become subjects of their own. This feminist appropriation of the stereotype of the hysteric thus underlines the political motives of Irigaray’s philosophy.

I would like to use Irigaray’s strategic essentialist method of mimesis in this article, since I find it such a powerful strategy. The concept of singing hysterically or »chanter hystérique« that has come up a couple of times already, is obviously inspired by Irigaray’s hysterical mimesis and strategic essentialism.6 The potential singing sirens that will follow now, are involved in miming the female hysteric, and many other stereotypes associated with hysteria, such as the neurotic housewife and the hypersexualized woman. But whereas Irigaray attacks phallogocentric thought on a theoretical level, these female artists will, as I hope to show now, take on these stereotypes in a lyrical and performative manner. They sing in a hysterical and subversive manner, and it is this cultural materialization of »chanter hystérique« that could be seen as potentially feminist, or so I will argue.

»Chanter hystérique«:

The strategic reconstruction and subversive deconstruction of hysteria in the oeuvres of Peaches, Amanda Palmer, and PJ Harvey

We can now explore how Peaches, Amanda Palmer and PJ Harvey engage in the practice of singing hysterically. If the latter go beyond Minaj’s and Gaga’s mere copying of hysteria, then we might be able to call their oeuvres feminist in the political sense. But this does not mean that these potential singing sirens all have openly labeled themselves as feminists: Harvey, for instance, once stated that she never felt the need to express that she was a feminist (Raphael 2009). And Amanda Palmer – formerly known as the lead vocalist and pianist of the Brechtian punk cabaret band The Dresden Dolls – has even been accused of exploiting feminism by taking on a feminist identity for its shock value. Peaches, on the other hand, might be the most forthright feminist of the group: as a queer artist, she frequently talks about the political importance of feminism. And although Peaches’ lyrics are extremely explicit, she writes them that way to criticize the double standard in rap when it comes to female representation. She uses her songs to reverse the objectification of women, as can be heard on her second album »Fatherfucker« (2003).

The latter title was deliberately chosen, and tells us how Peaches gives her oeuvre a political feminist meaning, as can be seen in the next quote:

The term ›motherfucker‹ is so over […]. It’s used every day by everybody. You would probably even call your mother a ›motherfucker‹ – and it would mean absolutely nothing. But ›fatherfucker‹ is an incredible word. It’s time to put them on equal terms. (Peaches in Paoletta 2003: 33)

Even though Peaches’ stance on sexual equality politics might be more outspoken than Harvey’s and Palmer’s, I argue that each of the aforementioned oeuvres has some hidden feminist features. Next to that, these oeuvres can be separated along the lines of an Irigarayian methodology – without however creating a feminist hierarchy in which one of the oeuvres would be seen as more significant than the other.

As shown before, Irigaray’s hysterical miming of phallogocentric discourses works on two levels: Irigaray appropriates the image of the hysteric in a strategically essentialist way, and then approaches these discourses in a subversive manner. In a later phase, Irigaray moves beyond phallogocentrism, after having subverted its stereotypes from within. Both of these phases are equally important: without the first deconstructive phase, there would obviously be no room for Irigaray’s (re)construction of a »parler femme«.

In what follows, I will read the oeuvres of Peaches, Palmer and Harvey along these lines, arguing that especially the latter oeuvre suits an Irigarayian rereading.

Singing sirens and (post)feminism.

Peaches’ gender-bending machismo and Palmer’s (post)feminist provocations.

Peaches’ lyrics are sexually explicit, to say the least: songs such as »AA XXX« and »Diddle My Skittle« do not require further textual analysis to realize that (Peaches 2000). Because of these constant sexual innuendos, Peaches has been criticized a lot. When asked about the negative feminist reactions to her music, she stated the following:

I would hate to be just loved. It’s great to have both opinions. I like that people have something to discuss rather than just, ›Oh, I like that song.‹ (Peaches in Meter 2003)

Peaches is a provocateur, and her radical queer politics is noticeable every song she has ever written: »Two Guys (For Every Girl)« from »Impeach My Bush« (2006), for example, shows us how Peaches queers the masculinized concept of a threesome, and bends it into a more feminist-like arrangement. Peaches’ politics obviously focuses on a playful form of sexual liberation, yet, she has a more serious feminist side, too. In the video for »Set It Off«, a song from her kinky electro album »The Teaches Of Peaches« (2000), Peaches is the spectator of a couple of gender-bending sexual activities in a club’s bathroom. All dolled up in tiny pink panties, she is dancing and having a good time. But at the end of the video, Peaches undresses herself, whilst her body hair starts to grow in an uncontrollable manner – implying that Peaches here provocatively mocks the stereotypical representation of women in music videos, and female beauty standards in general.

Amanda Palmer also knows the tricks of provoking all too well: »Oasis«, an autobiographical song featured on «Who Killed Amanda Palmer« (2008), for instance, is a provocative track about date rape and abortion, cheerfully sung by Palmer, who downplays the gravitas of her tragic situation, because she received a letter from her favorite band. »Oasis« portrays Palmer as an independent woman who sees abortion as an acquired right.

The latter of course could make us wonder whether Palmer is more of a postfeminist – in the sense that one thinks that feminism is now politically and culturally outdated – than a feminist. In an interview I had with her in 2008, Palmer criticized some of the postfeminist tendencies in the media and the music industry in particular, stating that our political landscape had »evolved from an equality feminism into an antifeminism that focuses on a false sense of empowerment« (Palmer in Geerts 2008).

But in a later interview, Palmer contrastingly critiqued contemporary feminism for its ineffectiveness by arguing that we should focus on »individual empowerment« (Palmer in Geerts 2010) instead of holding onto theoretical feminist doctrines. Palmer thus seems to be moving towards a more individualist, DIY-feminism, without neglecting the more traditional feminist topics, however. Songs about female autonomy such as »Oasis« and »Ampersand« are for instance feminist in a traditional, equality politics’ perspective (Palmer 2008). And like Peaches, Palmer constructs a radical sexual politics of her own: she touches upon issues such as intersexuality in »Half-Jack« (The Dresden Dolls 2003), and in one of her more recent songs, »Map Of Tasmania«, Palmer even tackles the horrors of female shaving (»I say grow that shit like a jungle, give ‘m something strong to hold onto. Let it fly in the open wind, if it gets too bushy, you can trim«) (Palmer 2011).

Both Peaches and Palmer nonetheless seem to be postfeminists, in the sense that they suggest that the days of feminism as a grand political project are long gone, and that it is now time for a more playful, DIY-feminism. Could they then still be categorized as singing sirens? Peaches’ oeuvre, for starters, could be reread in an Irigarayian way. Peaches’ strategy seems similar to Irigaray’s mimesis: in »Stick It To The Pimp« (Peaches 2006), Peaches hysterically mimes and parodies the stereotypical representation of women in hip hop as bitches and hoes.

By reappropriating the term bitch and associating it with female desire, and by transforming herself into a female pimp who enslaves male pimps, Peaches successfully deconstructs hip hop’s masculine symbolic. In contrast to feminist thinker Audre Lorde, Peaches suggests that the master’s tools can in fact dismantle the master’s house, and she not only challenges the patriarchal domains of hip hop and rap in her oeuvre, but also plays with the machismo and the phallic fetishization of the guitar in rock (also see James 2009). Her reappropriation and reconstruction of machismo into machisma, can already be seen in »Rock ‘n Roll« from »Fatherfucker«, where Peaches endlessly repeats the same guitar riff, whilst hysterically screaming the words rock ‘n roll.

And the same kind of strategic mimesis takes place in Palmer’s oeuvre. Palmer’s cover of Rodgers’ and Hammerstein’s »What’s The Use of Wond’rin’?« serves as a perfect example (Palmer 2008): Palmer heavily focuses on the issue of domestic violence in the accompanying video, which opens with the image of two neurotic and eagerly cooking housewives.

Amanda Palmer in »What’s The Use of Wond’rin’?«.

Amanda Palmer in »What’s The Use of Wond’rin’?«.

Pictures taken from the music video by Amanda Palmer performing What’s The Use Of Won’drin‘. (C) 2009 Amanda Palmer and Michael Pope

We are then confronted by a scene that shows the husband of Palmer’s character screaming and yelling, and a later scene in which Palmer’s character appears to have been beaten up. Palmer at first sight seems to be repeating the passive victimization of the female lead character in the original song. But she actually goes one step further, and this becomes apparent in the last scene, where her character and the other housewife happily sit around the table, after having skinned the abusive husband alive.

Palmer is nonetheless countering patriarchal violence with violence here, and the same can be said about Peaches’ mimesis: Peaches tries to revalue women by freeing them from the concept of motherfucker, yet replaces the latter with an equally reductive concept. This tells us that Peaches and Palmer are mainly operating within Irigaray’s more deconstructive mimetic phase. A comparison between Irigaray’s and queer philosopher Judith Butler’s ideas about mimesis could help us understand this better, since both artists, like Butler, are not going far enough when it comes to mimesis. The difference between Irigaray’s and Butler’s strategy of mimesis has been articulated as follows:

Mimesis, for Irigaray […] is also a conscious and playful strategy for revealing the place of the feminine within language. Butler also suggests that mimesis is a strategy. However, for Butler there is no subject, feminine or otherwise, that is revealed through mimesis. Instead, gender is a performative cultural fiction, constructed through a Foucauldian law. (Campbell 2005: 345)

Although one should keep in mind that Butler’s mimetic strategy was partially inspired by Irigaray’s philosophy, it is nonetheless clear that she never moves towards a feminist identity politics via hysterical mimesis.7 This does not necessarily mean that Peaches and Amanda Palmer cannot be seen as singing sirens: they do take up a mimetic strategy similar to Irigaray, as to deconstruct stereotypes associated with women by repeating them strategically. Their lyrics and performances are of an immense feminist potential, since they, unlike Minaj’s and Gaga’s, go beyond merely playing with deconstruction, and thus successfully avoid the stereotypical cliché-confirming imagery the latter ended up in. But rereading these oeuvres through Irigaray’s second mimetic phase, nonetheless seems to be impossible: like Butler, Peaches and Palmer are unable to construct a feminist politics outside phallogocentrism.

Conclusion.

PJ Harvey and a female Imaginary. 50 Ft Queenie feminism as political feminism’s newest paradigm?

But what about Harvey’s oeuvre? Does she take it a step further than Peaches and Palmer? Harvey’s representation of femininity, for starters, is quite remarkable. In contrast to music theorist Mark Mazullo, who argues that Harvey subverts gender norms by creating an »androgynous persona« (Mazullo 2001: 432), I would like to claim that Harvey appears to obsessed with creating an überfeminine image instead, as can be seen throughout her artistic career.8 Take the album cover of »Dry« (1992), for instance: we see Harvey’s face, covered in smeared-out lipstick. That image, combined with the back-cover photo of a red-colored lipstick, suggests that Harvey addresses questions of femininity and beauty standards in her works.

This can be further supported by »Dress«, a song that talks about the hardships of being a woman and having to conform to rigorous beauty norms (Harvey 1992). But Harvey does more than just criticize these beauty ideals, as can be seen in the video clip that accompanied »50 Ft Queenie« (Harvey 1993a): there, she makes fun of symbols of femininity by wearing over-sized sunglasses, high-heeled golden shoes, and clutching onto a gigantic golden bag – an accessory that is only fully shown on the cover of the single.

There is an immense sense of playfulness attached to Harvey’s image here, and her onstage performances from those days reflected that too, since Harvey tended to perform in flashy dresses and feathery boas. Harvey once commented on this issue in an interview, saying that »these costumes aren’t sexy […]. They are ridiculous. They’re funny« (Frost 1993: 52). Harvey thus engages with these symbols of excessive femininity in an ironic manner, and this became especially clear with the release of »To Bring You My Love« (1995). Harvey at that time took on a vampiristic femme fatale look that bordered on pure drag, by wearing tons of make-up, blood-red lipstick, gothic gowns and pink cat suits.

This femme fatale look clashes with Harvey’s more Victorian-looking persona during the »White Chalk«-era, which tells us that her excessive feminine style is more than just a gimmick: one could in fact reread Harvey’s excessive feminine imagery through an Irigarayian perspective. Harvey, with her boas and gothic, almost clownish-looking make-up, and later with her Victorian imagery, playfully mimes several patriarchal stereotypes, deconstructs them, and attaches a feminist message to them as well.

The latter can be seen if we take a look at the lyrics of »50 Ft Queenie« where she sings about being »one big queen. […] Second to no one« (Harvey 1993a); a queen that rules the world, and that dominates all the Casanovas. Harvey’s 50 Ft Queenie feminism seems to be opening up a space for a playful articulation of an autonomous female sexuality here, which sounds very Irigarayian. This element already suggests that Harvey’s oeuvre moves beyond the mere playful deconstruction of stereotypes, beyond the deconstructive mimetic phase: there is a feminist political potential to be found in her »chanter hystérique«.

If we briefly look at Luce Irigaray’s feminine and feminist philosophy, one will probably find it easier to understand what that feminist potential looks like exactly. Irigaray’s philosophy goes beyond phallogocentrism by deconstructing female clichés – a deconstruction that opens up a space for a different female Imaginary and a »parler femme. Next to focusing on these issues, Irigaray accentuates the need for an articulation of female subjectivity, an adequate representation of female specificity and sexuality, and a feminist identity politics.

It is unnecessary to completely summarize Irigaray’s feminist politics here, but what is important to know, is that there can be no female subjectivity, identity, and feminist politics if we cannot find access to a non-phallic, female Imaginary (see e.g. Irigaray 1974/1985a: 30). Irigaray’s reconceptualized female Imaginary usually focuses on restoring female genealogies – relationships between mothers, daughters and sisters that have been suppressed in patriarchal culture – by articulating concrete images of the bond between the latter (Irigaray 1977/1985b). This aspect is central to Harvey’s oeuvre as well: in »To Talk To You« (Harvey 2007), for instance, Harvey talks to her late grandmother, saying how much she misses and needs her.

But the most important facet of Irigaray’s female Imaginary is her anti-Freudian argument that female sexuality is something that exists on its own: the problem, according to Irigaray, is that women have always been seen and represented as mirrors, as bodies-for-men. »Commodities, women, are a mirror of the value for men« (Irigaray 1977/1985b: 177), which means that the female sexual body has always been seen as commoditized by men. Yet, women’s sexuality and her experiences of it are much more multi-faceted than what men (like Freud and Lacan) have made of it, in Irigaray’s eyes: a woman’s sexuality breaks out of the phallic standard; her sexuality is always »at least double«. She has »sex organs more or less everywhere«, and » […] the geography of her pleasure is far more diversified« than male sexuality that is usually phallic-focused (ibid.: 26). And this exactly what Irigaray tries to show us with her feminine symbol of the two lips.

What Irigaray states here is that women are sexual creatures, too, instead of the passive, penetrable objects of Freudian psychoanalysis: they have desires and can feel lust. It is this idea of a self-asserting feeling of lust that is omnipresent in Harvey’s oeuvre as well. Songs such as »I Can Hardly Wait« (Harvey 1993b) and »Catherine« (Harvey 1998) articulate female desire in its purest and most diverse forms.

»This Is Love«, on the other hand, is a pure lust song, in which the protagonist chases her lover round the table (Harvey 2000). And together with »Rid Of Me« (Harvey 1993a), these songs express the voice of a woman that knows what she wants, sexually speaking; a woman that by the way seems to be completely in control, without being objectified or objectifying someone else.

The last song I want to focus on in this conclusion is one of Harvey’s earliest songs, »Happy & Bleeding«, taken from »Dry«. »Happy & Bleeding» can literally be seen as the archetype of what is meant by Irigaray’s constructive phase of mimesis, and can hence be considered as an »écriture féminine« song pur sang.

In this song, Harvey namely explores the topic of menstruation – an aspect of the female sexual body long regarded as taboo. Irigaray refers to menstrual blood in all her works, too: in its patriarchal connotation, menstrual blood signifies that a girl is ready to be exchanged and used as a commodity (see e.g. Irigaray 1977/1985b). But in Irigaray’s female Imaginary, woman’s »red blood« (ibid.: 186) is a symbol of her sexual autonomy, and of her relationship with her mother. And it is exactly that idea of autonomy that we can read into Harvey’s lyrics, when she states that she’s »happy and bleeding« (Harvey 1992).

All of the previously encountered images of the (grand)mother and (grand)daughter relationship, female sexuality, lust and desire, and the revaluation of the female body with all of its bodily features, are part of the female Imaginary that Irigaray is trying to (re)construct in her philosophical oeuvre. Because of the fact that these positive symbols of femininity are present in PJ Harvey’s lyrics and videos, and because these symbols are exactly the ones Irigaray uses to construct her feminine and feminist identity politics, I would like to claim that PJ Harvey’s oeuvre indeed can be read as politically feminist. Or rephrased in Irigarayian terms: PJ Harvey does not only speak or sing hysterically, but also »speaks as a woman«.

This does not mean that I want to label Harvey’s 50 Ft Queenie feminism as today’s key feminist political paradigm – I am fully conscious of the fact that the kind of feminist model presented here merely exists out of separate acts of meaning disruption. There is obviously still an immense gap between the critical feminist moments in Harvey’s oeuvre and feminist activism and gender politics in real life, but by analyzing Harvey’s oeuvre through an Irigarayian perspective, one can see how at least some of today’s popular female artists are creating pop cultural artifacts that are tentatively challenging the deeply-rooted patriarchal stereotypes about women.

And it are these feminist artifacts that could eventually inspire other artists, musicians, and feminist thinkers and activists, to establish a feminist politics that addresses the specificity of female subjectivity and sexuality in a non-stereotypical manner. Harvey, together with the other two aforementioned singing sirens, might not be the new heralds of an all-encompassing political feminism of the 21st century, but a critical rereading of their oeuvres, or the cultural artifacts they have produced during their careers, at least stimulates us to continuously reflect upon how we in our postfeminist society and culture deal with certain stereotypes about women, beauty standards and normative gender roles. The least we can do, is let ourselves be seduced by these hysterically singing sirens, and see where that takes us.

Endnotes

1 When talking about songs or music videos, I will only refer to the artist’s album that these songs are featured on in the bibliography.

2 The concept of women’s music could be seen as problematic, because of its essentialist connotations, but I will use it anyway to refer to specific kinds of pop cultural artifacts created by female artists.

3 When talking about hysteria in this article, I do not only wish to refer to the Freudian psychoanalytical construction of this phenomenon as a disease that solely affected women (see e.g. Freud 1895/1955, 1896/1953 and 1905/1953 for Freud’s and Joseph Breuer’s stereotypical ideas about women as passive subjects, easily falling prey to hysteria, but I also want to focus on Luce Irigaray’s reconceptualization of hysteria as something that potentially disrupts these traditional, psychoanalytical views on hysteria. I will come back to Irigaray’s ideas shortly in the main text, but the idea that hysteria also has a potential feminist undertone, or could be reconceptualized as a feminist tool of resistance against patriarchy, has also been claimed by other feminist thinkers. See for instance Diane Herndl, who stated that »[h]ysteria is seen as kind of a ›body language‹ meant to express a feminist rejection of an oppressive ›cultural identity‹ […].« (Herndl 1988: 54). Or see French philosopher Hélène Cixous’ »The Newly Born Woman« (1975/1996), co-written with Catherine Clément, in which Cixous described the hysteric as a protofeminist, because she refuses to conform to certain patriarchal societal norms.

4 The idea that hysteria should be seen as a socially constructed pathology is in fact a Foucauldian idea as well. In »The History of Sexuality. Volume 1. An Introduction« (1976/1990), Foucault emphasizes that particularly female bodies have been hystericized, but he never really engages with the reasons why this process was so gendered. Elaine Showalter, on the other hand, does touch upon the reasons why women became the primary victims of this disease in »Hysteria, Feminism, and Gender« (Showalter 1993).

5 Phallogocentric thought – a concept that Irigaray borrowed from Jacques Derrida – started with Plato’s metaphysics, since Plato committed the first metaphysical matricide by ignoring the female origins of mankind, or the womb, in his epistemology. Phallogocentrism stands for a patriarchal system of thought, based on masculine identity, subjectivity and symmetry. It has »reduce[d] all others to the economy of the Same«, and ignores the existence of sexual difference between male and female subjects (Irigaray, 1977/1985b: 74). By looking at how »the unconscious« works in phallogocentrism, and by unraveling the »silences« or the muted female voices, Irigaray tries to the destabilize phallogocentrism, in order to come to a feminine philosophy that focuses on an ethics of sexual difference (ibid.: 75).

6 Irigaray does not use the concept of »chanter hystérique«, but she sometimes refers to singing as a prefiguration of »parler femme«, as can be seen in »Elemental Passions« (1982/1992).

7 Irigaray’s influence on Judith Butler is evident throughout Butler’s »Gender Trouble« (1990/2006): Butler there makes use of a lot of Irigarayian concepts and ideas, such as sexual difference, mimesis, and Irigaray’s critique of phallogocentrism. But she also criticizes Irigaray for her apparent biological essentialism (see ibid.: 41). And Butler also does not agree with Irigaray’s feminist politics that wants to move beyond phallogocentrism, since she considers such a politics to be naïve.

8 The same claim has more or less been made by Mélisse Lafrance in Burns/Lafrance 2002: 169-170. In this chapter, Lafrance is very critical of how Harvey deals with femininity in her oeuvre, whereas I will try to read this imagery in a more positive manner.

Literature

Bauer, Nancy (2010): Lady Power, in: The Opinionator. Exclusive Online Commentary from The Times, 20th of June, http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/20/lady-power/.

Burns, Lori/Lafrance, Mélisse (eds.) (2002): Disruptive Divas. Feminism, Identity & Popular Music, New York and London.

Butler, Judith (2006): Gender Trouble. Feminism and the Subversion of Identity [1990], New York and London.

Campbell, Jane (2005): Hysteria, mimesis and the phenomenological imaginary, in: Textual Practice 19, pp. 331-351.

Cixous, Hélène/Clément, Catherine (1996): The Newly Born Woman [La jeune née (1975)], London.

Foucault, Michel (1990): The History of Sexuality. Volume 1. An Introduction [Histoire de la sexualité. Tome 1. La volonté de savoir (1976)], New York.

Freud, Sigmund (1995): Studies on Hysteria [Studien über Hysterie (1985)], in: James Strachey (ed.): The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Volume II (1893-1895). Studies on Hysteria i-vi, London.

Freud, Sigmund (1953): The Aetiology of Hysteria [Zur Ätiologie Der Hysterie (1986)], in: James Strachey (ed.): The Standard Edition Of The Complete Psychological Works Of Sigmund Freud. Volume III (1893-1899). Early Psycho-Analytic Publications, London.

Freud, Sigmund (1953): Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria [Bruchstück einer Hysterie-Analyse (1905)], in: James Strachey (ed.): The Standard Edition Of The Complete Psychological Works Of Sigmund Freud. Volume VII (1901-1905). A Case of Hysteria, Three Essays On Sexuality, and Other Works, London.

Frost, Deborah (1993): Primed and ticking, in: Rolling Stone 663, pp. 52-55.

Geerts, Evelien (2008): Echt ingepalmd door Amanda Palmer [Echt taken over by Amanda Palmer], in: Echt 10, p. 21.

Geerts, Evelien (2010): Interview met Amanda Palmer en Jason Webley (Evelyn Evelyn). Over Duvels drinken en konten knijpen [Interview with Amanda Palmer and Jason Webley (Evelyn Evelyn). Drinking Duvels and pinching asses], in: Indiestyle, May, http://www.indiestyle.nl/InterviewmetAmandaPalmerenJasonWebleyEvely/tabid/9186/language/nl-NL/Default.aspx [Link mittlerweile erloschen].

Halberstam, J. Jack (2012): Gaga Feminism. Sex, Gender and the End of the Normal, Boston.

Herndl, Diana Price (1988): The Writing Cure. Charlotte Perkins, Anna O., and ›Hysterical‹ Writing, in: NWSA Journal 1, pp. 52-74.

Irigaray, Luce (1985a): Speculum of the other woman [Speculum de l’autre femme (1974)], Ithaca.

Irigaray, Luce (1985b): This sex which is not one [Ce sexe qui n’en est pas un (1977)], Ithaca.

Irigaray, Luce (1992): Elemental Passions [Passions élémentaires (1982)], New York.

James, Robin M. (2009): Autonomy, Universality, and Playing the Guitar. On the Politics and Aesthetics of Contemporary Feminist Deployments of the ›Master’s Tools‹, in: Hypatia 24, pp. 77-98.

Lady Gaga and Lydverket (2009): Interview with Lydverket, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e0VQDOAxO0I.

Mazullo, Mark (2001): Revisiting the wreck. PJ Harvey’s Dry and the drowned virgin-whore, in: Popular Music 20, pp. 431-447.

McClary, Susan (2000): Women and Music on the Verge of the New Millennium, in: Signs 25, pp. 1283-1286.

Meter, William V. (2003): Peaches. She’s a Very Kinky Girl, in: Spin, 23rd of June, http://www.spin.com/articles/peaches-shes-very-kinky-girl.

Paglia, Camille (2010): Lady Gaga and the death of sex, in: Sunday Times Magazine, 9th of December, http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/public/magazine/article389697.ece.

Paoletta, Michael (2003): Peaches Seeks Sexual Equality On New Disc, in: Billboard 115, p. 33.

Plaza, Monique (1980): ›Phallomorphic‹ power and the psychology of ›woman‹, in: Gender Issues 1, pp. 71-102.

Raphael, Amy (2009): Shy girl or she-wolf? Will the real Polly Harvey please stand up, in: The Guardian. The Observer, 3rd of July, http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2009/mar/08/pj-harvey-interview.

Showalter, Elaine (1993): Hysteria, Feminism, and Gender, in: Sander L. Gilman/Helen King/Roy Porter/G. S. Rousseau/Elaine Showalter (eds.): Hysteria Beyond Freud, Berkeley, Los Angeles and London, pp. 286-344.

Whitney, Jennifer Dawn (2012): Some Assembly Required. Black Barbie and the Fabrication of Nicki Minaj, in: Girlhood Studies 5, pp. 141-159.

Williams, Noelle (2010): Is Lady Gaga a Feminist or Isn’t She?, in: Ms. Blog Magazine, 3rd of November, http://msmagazine.com/blog/blog/2010/03/11/is-lady-gaga-a-feminist-or-isnt-she/.

Music albums

Amanda Palmer (2008): Who Killed Amanda Palmer; Roadrunner.

Amanda Palmer (2011): Amanda Palmer Goes Down Under; Liberator Music and self-released.

Azealia Banks (2012): 1991; Interscope.

Iggy Azalea (2011): Ignorant Art, self-released.

Lady Gaga (2008): The Fame; Streamline, Kon Live, Cherrytree and Interscope.

Lady Gaga (2009): The Fame Monster; Streamline, Kon Live, Cherrytree and Interscope.

Lady Gaga (2011): Born This Way; Streamline, Interscope and Kon Live.

Ludacris (2010): The Battle Of The Sexes; DTP and Def Jam.

Nicki Minaj (2010): Pink Friday; Young Money, Cash Money and Universal Motownlabels.

Peaches (2000): The Teaches Of Peaches; Kitty-Yo.

Peaches (2003): Fatherfucker; XL Recordings.

Peaches (2006): Impeach My Bush; XL Recordings.

Pink (2006): I’m Not Dead; LaFace, Zomba and Jive.

PJ Harvey (1992): Dry; Too Pure and Indigo.

PJ Harvey (1993a): Rid of Me; Island.

PJ Harvey (1993b): 4-Track Demos; Island.

PJ Harvey (1995): To Bring You My Love; Island.

PJ Harvey (1998): Is This Desire?; Island.

PJ Harvey (2000): Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea; Island.

PJ Harvey (2007): White Chalk; Island.

The Dresden Dolls (2003): The Dresden Dolls; 8 Ft. Records and Roadrunner.

Evelien Geerts, Graduate Gender Programme, Utrecht University